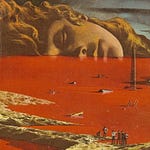

Welcome to Wonderland. This series will present a coherent philosophical framework from the bottom-up. Starting with the value of philosophy itself and then exploring the realms of metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and morality. The second half then dives into political theory and investigates the subsequent functions and role government. As the root of all ideas is philosophy, we are going to start off with that. The question today being, what is philosophy? And who needs it? My answer is everyone, and I am going to try to convince you why. Let’s start off with a story…

Part #1. The Maze

I want you to imagine that you are lying in a sunny field, and out of the corner of your eye you spot a flash of white. You sit up, and realize it’s a rabbit, in a waistcoat, with a pocket watch. Knowing where this story goes you chase after it, and soon find yourself tumbling down into Wonderland. But, upon landing, you quickly realize it is not at all what you expected. There is no hallway full of doors, or table with instructional food. Instead, you find yourself in a completely novel place. You have wound up somewhere inside of a great hedge maze. The walls of which are too tall to climb or see over, and too dense to pass easily through. You explore a little, looking for the white rabbit, or at least a way out, but find nothing. Just a seemingly endless array of hedges and pathways going off in every direction. You start to worry. “What have I gotten myself into?” you wonder. And you look around, with three questions on your mind:

Where am I?

How can I discover it?

What should I do?

Alright, let’s pause and talk about what any of this has to do with philosophy. Now, the maze in this story is going to be a metaphor for life. Just like Alice lost in Wonderland, we have all found ourselves thrust into this big, beautiful, confusing world, and are doing our best to discover what rules govern it, what tools we can use to explore it, and what on earth we should do while we are here. The questions you must confront upon finding yourself lost in Wonderland are the same questions every person must consider living here, on earth.

Of course, some people would say that the answers are self-evident. Where am I? Well, I live in Canada. How do I know it? Oh, it’s obvious! Just look around. What should I do? Hmm, well that one is a little trickier, but, probably whatever everyone else is doing? Or whatever I’m told? The only problem is that these answers are not very meaningful or fulfilling. They speak to the elements of our daily lives which are superficial, rather than fundamental. And they are completely unhelpful the moment you find yourself in a novel situation, like lost in a maze. This is because the conventional answers speak only to the contextual nature of the world you are living in—not the fundamental one.

Philosophy is the study of the fundamental nature of existence, of ourselves, and of our relationship to existence. You might notice that these three areas align with the three questions posed in Wonderland, and they represent the three primary domains of philosophy.

The study of the fundamental nature of existence is known as metaphysics, the answer to the question, “Where am I?” Metaphysics asks: are there firm and stable laws which regulate the universe? Or are things entirely relative and relational? Is there a consistent, coherent structure to reality? Or is everything random and chaotic? Does reality exist independent of our minds? Or as a product of it? The nature of your actions, attitudes, and ambitions will differ according to which set of answers you come to accept. But no matter what set of conclusions you reach, you will be confronted by a corollary question: “How do I know it?”

Epistemology is the study of our relationship to existence and how we acquire knowledge, the answer to the question, “How can I discover it?” Epistemology asks: is it possible to acquire knowledge about the nature of reality? And if so, how? Are our senses reliable tools to navigate the world? Or are they easily influenced and impressionable? Do we learn through reason, or revelation? Are our emotions and intuitions valuable sources of information? Or are they irrational and fallible?

From these two branches, a third emerges: ethics, which is the study of ourselves and what constitutes moral action. The answer to the question “What should I do?” Ethics asks: is moral action possible, or desirable? And if so, what does it look like?

So, if the maze is a metaphor for life, and philosophy is represented by the questions you must confront in order to escape the maze, then this story is going to demonstrate the consequences of different sets of belief. Either reality exists to be contended with, or it does not. Either we are capable of acquiring knowledge about the world, or we are not. Either we can act in a way which is purposeful and productive, or we can not. Now you would think that these basic yes or no questions should have obvious answers, but right now we live in a world where we can’t even get on the same page about the fundamentals. Philosophy does not represent some abstract realm of questions without consequences, you are operating by a philosophy right now, whether you realize it or not. And the answers that you come to accept will have a direct impact not only on your course of your own life, but also the lives of people around you, and, quite possibly, the fate of the world. So, let’s return to the maze and examine some of those consequences.

Part #2. Deny

You are currently lost inside of a great hedge maze, looking for a way out. You wander around for ages, but the further you go the more vast and complex the maze seems to become. You walk for hours, not knowing if you are moving closer to, or further away from a potential escape. Or maybe you are simply caught in a loop, retracing old steps without even realizing it and making no progress whatsoever. Eventually, after a few frustrating hours, you decide to stop and have a rest, considering the strange series of events that brought you here: chasing the white rabbit down into the hole, and discovering a whole new world that seems to be ruled by neither rhyme nor reason. Suddenly it all makes sense, you realize that you must be dreaming. Of course! There is no such thing as Wonderland, what were you thinking? I’ll just pinch myself and wake up, you decide. You spend a good five minutes trying to wake up but nothing works. You start to panic. Where am I?! You wonder once again. How did I get here? How do I get out? Can I get out? How do I know any of this is even real? None of it makes any sense! If I am not dreaming then am I in some sort of sadistic simulation? Or, maybe I have died and gone to hell, destined to an eternity of trying to escape an endless maze… like Sisyphus. You feel trapped, helpless, hopeless, and confused. Overwhelmed by the vast and complex, nature of the world you have found yourself stuck in, you do the only thing you can do: you curl up into a ball on the ground and begin to bawl yourself. Eventually, night starts to fall, and you can feel your stomach growling with hunger. But you ignore it, you have no interest in moving or looking for food or water. You have decided to accept the inevitable and surrender yourself to the mercy of the maze. Days pass by, and, eventually, you pass out for good.

Alright, let’s pause again. Now, this outcome might sound a bit stupid, but it represents something important; this is what happens when you refuse to accept reality on reality’s terms. When you deny a metaphysical understanding of the universe. Winding up in Wonderland without any clue what to do, the first thing you might do is question the nature of your reality. Thrust into a world that feels too overwhelming to understand, your first instinct may be to insist that it cannot be understood at all. You might want to tell yourself that you are dreaming, or living in a simulation, or any other story that exonerates you from having to discover where you are. Life is vast and complex, and it may seem easier to try to deny it, to surrender yourself to the causal forces of the universe rather than attempt to master them. But, clearly this method is not very effective. To deny existence is to become a victim to it. You are alive, you are in a maze, that means something real. You can try to avoid that truth, to make it into something different or more palatable, to avoid the responsibilities of having to think or act. But ultimately, the consequences of reality will catch up with you. Better to try to contend with them a little first. So, let’s try again.

Part #3. Might

You wake up back in the maze, surprised to discover that the thirst, hunger, and deterioration from the previous days has vanished. Your body seems to have returned to the state it was in when you first entered wonderland. Renewed with new energy, and, being familiar with the plot of groundhog day, you decide that there must be some way to conquer the maze, since, apparently, you wont die trying. You choose a new strategy; instead of wandering aimlessly, you decide to pick one straight path and commit to it—no matter what gets in your way. You walk forward for a little while and pretty soon encounter a hedge. But instead of trying to go around it, you start to force your way through it, and begin the painstaking process of ripping apart leaves and twigs and branches, eventually creating enough room that you can squeeze your body through and out, onto the other side, acquiring a few scratches along the way. It is not long until you encounter another hedge and have to repeat the same tedious process all over again. After a dozen more iterations of this your entire body is covered in scratches and your hands are red and raw. But you persevere, determined to make it out alive or die trying, emerging from each hedge more shredded and bloodied than the one before, as twigs catch on and tear at open wounds. Yet every time you grow weak and willing to surrender, you simply turn around and look at how much progress you have made, and that knowledge gives you the courage to continue. Finally, after days without food or water, you begin to break through a hedge and reveal an open field on the other side. You joyously force your way through this last hedge and tumble out of the maze, collapsing on the other side exhausted but victorious. You decide to rest for a moment and close your eyes, enjoying your newfound freedom. Unintentionally, you drift off, and when you wake up you are overwhelmed by a sense of dread, as you realize that your wounds have healed, and you are once again back where you started: lost in the middle of the maze. However this time, the walls have turned to stone—you’re not going to get away with that again.

So, what are the philosophical implications of this second strategy? Well, you have realized the need to accept and contend with reality, rather than deny it, but you are refusing to play by the rules of the game. You have decided that the structure of the maze, the logic which dictates its form, is unimportant, since you have discovered a way to work around it. Therefore there is no need for you to acquire knowledge about the world, since you are able to manipulate its structure by sheer strength and force of will. But, as we all know, might is not right, since it is not a consistent principle. While forcing reality may reap you rewards in some circumstances, it is an unreliable tool. Your success was an accident of your environment: if the walls had been made of stone to begin with, you’d still be just as lost as you were in the first scenario. You have not adopted an epistemology that allows you to gain any knowledge about the rules which govern your environment. Therefore the outcome you achieved, breaking through to that open field, was unearned. It is a bad guiding principle of behaviour since it cannot be transferred across different circumstances. You cheated reality rather than mastered it, and this method will only get you so far. People have different capacities for physical strength and strength alone does not demonstrate genuine capability, for it is randomly distributed and inconsistently effective. Moreover this brutal process of forcing reality to bend to your whims is agonizing to engage in. It does not feel right because it is not right, and it doesn’t last. We all know this. It’s like that old proverb of teaching a man to fish—if instead of learning how to fish yourself you go and kill the fisherman and eat his food. And then later you go hungry since now there is no one around who knows how to fish. In other words, force is unsustainable. Failure to adopt real solutions to problems means that you will continue to encounter them. This is because you have not discovered anything meaningful about the system you are in. Breaking apart the form of the maze for your temporary success does not solve the puzzle, you must abide by the rules of the game. Force alone is untethered to reliable knowledge or consistent principles, and is therefore not a viable solution. So, let’s try again.

Part #4. Rely

The hedges have turned to stone and you are lost once again. You are ready to cry out at the futility of it all when you notice something else is new. Lying on the ground in front of you is a scrap of paper. You pick it up, and are shocked to discover a list of directions. A series of “left’s”, “right’s”, and “straight ahead’s” running down the length of the page. It seems like someone is trying to help you out. Elated you immediately start racing through its prescribed path, running through the stone hallways with confidence and zeal. However it is not long until you encounter a problem—you reach a junction where the paper says you must go straight but only left or right are viable options. Did you possibly miss a step? Or take a wrong turn? You try to retrace your steps but quickly become frustrated as you realize that you have no clue when, where, or how you lost your way. Then you realize that maybe you didn’t even set off in the right direction. Since left and right are all a matter of perspective, if you had been facing the opposite way when you began you would have taken an entirely different path. You crumple the paper up in defeat, realizing that you are too far from your starting point for it to have any utility. Even if the instructions had been useful once, there is no way that you can apply them now that you are lost again. You chuck the note aside, but as you do another one flutters down, like a gift from God. This one, instead of relative directions, contains an objective drawing. An image of a maze. Finally, a guide with real utility! Since it doesn’t matter where you start, you can always orient yourself relative to the map to figure out where you ought to go next. you study the diagram and start trying to compare it to your surroundings, looking for key junctions or defining features which could help you get your bearings. You spend a few hours walking around looking for similarities between your maze and the paper one, trying to figure out where you are in relation to the map. But every time you think you have it figured out you take a turn and encounter some obstacle or pathway that is not accounted for in the paper analogue. Eventually, you are begrudgingly forced to admit that although you have a map of a maze, it is not a map of your maze. Any similarities are completely coincidental, and knowledge of one will not help you navigate the other.

Okay, time to pause and analyze. If the last scenario represented a rejection of knowledge in favour of might, then this one represents the problem of trying to acquire knowledge through appeals to mysticism. In other words, how information can be unreliable when gained through someone else’s authority, rather than your own. Now, it doesn’t really matter where these notes came from or how they got to you, they could have been left behind by other adventurers, or the product of divine intervention. The point is that they represent cultural norms, accepted values and inherited knowledge. While these guides may have been viable in one time, or in one circumstance, that does not necessarily mean that they carry over to your own. This is because in order to use these tools you have to start from a certain position (like the list of directions), or in a certain context (like the map). And while the maze is a metaphor for life, there is no reason to assume that any two mazes are alike. That is to say, the things that you need to do to achieve success in your own life may be very different than the process that worked for somebody else. Maybe some role model of yours says that the key to their success is going for a run every morning and meditating for an hour, but repeating those habits in your own life does not guarantee that you are going to have the same outcome. Similarly, many religious beliefs and practices come from a time very different than our own. While they may have had practical utility back then, it is important to be consistently questioning and evaluating to what extent those moral standards and norms still hold true. Systems of understanding that worked for a certain time, context, or circumstance, may very well now be outdated relics of the past. This is why blind obedience to authority is never an effective way to conduct yourself through life. You must be able to independently assess how useful or relevant a given idea is by comparing it to your objective reality. Instructions alone are not enough; we are looking for principles of solution, not prescribed paths. So, let’s try again.

Part #5. Right

Upon discovering that the map will not help you any more than the note that came before it, you are once again overwhelmed by a sense of dread and frustration. “If only there was a way to find the right path!”, you cry out. And as you say this an idea dawns upon you, an idea so elegant and so simple you are shocked you had not considered it before. What if, instead of adhering to a certain direction or form, as the notes had suggested, you adhere to a certain methodology. That is to say, a certain means of solution rather than a specific mode. To accept reality, and not attempt to deny it or wish it away. To accept the logic, the structure, the rigidity of the maze, rather than trying to cheat it through force, and to accept the uniqueness of your own circumstance, rather than trying to replicate the tactics that might have worked for others. To look for the consistent principles which will not vary depending upon the context you find yourself in. Where am I? I am lost in a maze. How can I discover it? Through my own senses and mind. What should I do? Use the tools available to me to commit myself to the only thing I know for sure: the rule of rules, the walls of the maze. Its limitations are its structure. The only clue you need to escape the maze is the maze itself. It creates its own rules. To discover them, you need only to commit yourself to the system you have found yourself in, and follow through. Put your right hand on the right wall of the maze and walk forward, allowing the structure itself guide you to where you need to go. It will be a long process, a tedious one, you will have to encounter every dead end in order to determine which direction will bring about a promising lead. But in doing so, you will eventually discover the way out. Strict adherence to this one consistent thread will guide you to where you need to go next. You are using the system itself to discover how you should navigate it. This is a first principle. One that works for all mazes, across all circumstances.

And this is what philosophy provides. A framework that teaches you not what to think, not where to go, but how to think; the process through which you can tether yourself to reality and in doing so navigate its structure for yourself. Through the commitment to metaphysical reality and epistemological capacity, a moral duty naturally arises. Follow that thread, that tether, that wall, wherever it may lead, and in doing so you will discover the nature of the world around you and how you ought act in it. My philosophy is committed to this principle of process: the notion of truth and our capacity for discovery. And once accepted, this premise cannot fail you. It is not based in your whims or your wants or what someone else told you, but the world exactly as it is. It is only once you have discovered this guiding principle, this thread of reasoning that pulls you forward, that you are finally able to escape the maze, and explore the rest of Wonderland.

And that is what will come next. Now that I have described what philosophy is, and why you need it, I will outline what exactly my philosophy looks like. I have demonstrated why I believe metaphysics and epistemology are necessary, but I have not yet described what my personal interpretation of those domains are, only that they exist to be known. So, in the next chapter I will talk about metaphysics. I have a commitment to reality, but what is the process through which reality unfolds? What are the rules of the game? How does the maze acquire its structure? What are the fix and flux points which combine to give us the forms we are familiar with? My answer is complexity theory.

Continue to Part 2: The Metaphysics of Complexity

Wonderland is a free publication that outlines a philosophy and political vision for the 22nd century. To support my work and receive updates on new posts, sign up for a free or paid subscription.

Share this post