We have already covered philosophy, metaphysics, and epistemology, so this is the chapter where we tackle ethics. Specifically, where do our ethical intuitions come from? Given what is and what we can know, what should we do? In other words, how can facts lead to values? The reason this chapter is subtitled, “Why Sam Harris and Jordan Peterson Disagree,” is because I believe that there is an issue which lies at the crux of our ethical interpretations which is often overlooked, this being the timeless tension between free will and determinism. It’s a topic that these two have discussed at great lengths on podcasts and panels throughout the years, but I don’t think either of them get it quite right. They consistently talk past each other and seem unable to reconcile their fundamental difference of view. So today I want to try to resolve that tension by showing how both of their positions go on to guide ethical reasoning and inform religious belief, hopefully providing some new insights along the way. To get started, let’s pick up from where we left off in Wonderland...

Part #1. Ant Fugue, Phew!

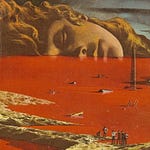

You hear the sound of marching. It fills you up like a crescendo, this swell in goose-step. In your mind’s eye you see an endless ant hill that goes off to infinity in all directions, with row upon row of worker ants marching in straight lines in quick succession, traversing the crests and slopes of the sand dunes. The scene reminds you of something you’ve seen before; hieroglyphs of ancient Egyptian slaves, hauling heavy loads uphill. An endless, unforgiving task, immortalized in the sandstone carvings of yesteryear. You are overwhelmed by the sense of an immense eternity. Your eyes fill with red and you wake up to a loud pounding in your ears, fading to a distant echo as you regain your senses. Where are you? You peel your eyes open in the blistering sun and are blinded by radiance as splashes of water spray through the air. You are lying on your back on the bank of some babbling brook in the middle of the woods. How did you get here? The last thing you remember was… Aunt Hillary.

You feel a swell in your skull as the pounding returns once more. You look around for a sign of the cottage but see nothing. The forest here seems different, darker, thicker. You have an eerie feeling that it’s been hours since your conversation at the cabin. Your legs are sore, as if you’ve been walking for quite a while, and you notice a collection of scratches and bruises that weren’t there before. Is it possible you lost time? Acquired a bout of accidental amnesia? How would one define such dissociative delirium? A funk of functional forgetfulness known as… Oh, a fugue, of course. You have a hazy memory of the book Aunt Hillary had shown you, with the words “Ant Fugue” written across the top of the chapter. Suddenly the strange series of events seemed suspiciously contrived. What could have triggered such an episode? You try to recall the conversation you had at the cottage. Aunt Hillary had been telling you something… what was it again? “The neurons in your brain are like the ants in my colony. Taken in isolation they possess no intelligence or agency, they are simply firing or foraging. Playing their small part in a much larger picture… So where are you? What are you?” If not your neurons or your nature or your nurture? How can you be anything more than the things you are made of?

Right. It was this idea that had first sent the blood rushing to your ears and formed a knot in the centre of your stomach. You had a vision of the moment of your conception as like the flick of a domino, leading you down a long chain of events that brought you to be here, now. Born as a baby with certain genetic and psychological predispositions, raised by your parents, influenced by friends and family, shaped by society… At what point did agency ever enter the picture? Did it? How could it have? You didn’t choose any of this. All of the choices you ever made were influenced by things you didn’t. Sure, maybe you got straight A’s in school, but you didn’t choose to be intelligent any more than you chose the colour of your hair. If you hadn’t been, would your failures be any more your fault than your successes? Surely if you had been born into someone else's body you would, by all logical consequences, be that person. There isn’t any meaningful standard to discriminate who you are now to who you could be if placed in someone else's shoes. Is there even any “you” that you could be referring to? Strip away all of those influences and experiences, and what’s left? Who’s home? How can you say that you are acting in the world, when really the world acted upon you first? Anything you could choose to do was determined by a million things you didn’t. So how can you say the choice was yours? All of your wants and wills were entirely predetermined. And what are you without them? Was there ever any you to begin with?

You start to again feel overwhelmed by a sense of existential horror. You realize that you aren’t in control of your next thought or action any more than a droplet of water controls its path downstream. It is simply fulfilling a prophecy that was set in motion by the grooves of the forest floor. You grasp aimlessly at psychological straws, trying to concoct some sort of standard that would allow you to prove your agency. But each moment a thought arises it is immediately dismissed as being predetermined. You can’t escape your mind any more than you can escape the world which built it. The pounding in your head returns with a vengeance and you can feel your breath begin to quicken as your mind races. You’re hyperventilating. A panic attack seems inevitable until you suddenly recall a series of breathing exercises you learned in a course on meditation. In through the nose, out through the mouth. Deep, shaky breaths. You try precariously to pull your focus away from the internal ego hemorrhaging and back out into the world. Listening to the sound of the surrounding forest. The wind in the trees, the babbling of the brook, the birdsong… Bringing your attention back to the present moment. Breathing in and out.

Ahh, that’s better. In this quiet state of awareness there is no need for agency. By emptying your conscious mind out like a cup, you allow the world to fill you to the brim. No need to think, or act, just be here now.

Part #2. Science, Spirituality, Sam Harris

The dream of the infinite ant colony is actually one I used to have all the time as a little kid. What was so memorable about it was that I would always wake up and continue to hear an intense pounding in my head for a few minutes. It would feel completely overwhelming and outside of my control, like I had been pulled into another world that lingered into my waking life. Of course, at the time I didn’t think it had anything to do with consciousness or determinism, but I think it’s interesting the sorts of connections you can draw in your life only after the fact. It’s an incredibly apt metaphor for describing the premise of todays discussion, which is determinism. The ants represent these infinite, interacting lines of causal progression, which stretch back to the beginning of time and forever into the distant future. As I described in the last chapter, they work the exact same way your brain does. From a materialist, scientific point of view, there is no real distinction between the two. The entire universe unfolds as one great big complex system, and you are not exempt from that equation.

To me, it has always been obvious that this must be the case. I was raised without any religious influences that would suggest I possess a soul which allows me to act independent from the outside world. Whatever you decide to do is, by neural necessity, the only thing you could have done in a given situation. However you can’t possibly be aware of all of the causes that are working to promote a given effect. Whatever decision ultimately arises in your mind is there for a myriad of reasons, both conscious and unconscious. For instance, when you are deciding what to eat at a restaurant, how many potential factors could be motivating your choice? Price point, food preference, placement on the menu, the temperature of the room, what you ate earlier that day, who you’re eating with… Maybe something else entirely! Maybe a little bit of all of those things. You may think that you ordered it by your own free will, and could just have easily ordered something else. But the simple fact that you made the choice that you did proves that there was some small causal factor that tipped the scales in a certain direction. Even when you are making a decision that is seemingly random, like picking a number between 1-100, some neural pathways are going to activate in your brain that cause you to say “67” rather than “76”. You don’t have to be aware of what these processes are for them to be acting in the background. You will still have the subjective experience that you are in charge of your actions (because you are), but the choices that you ultimately make will be, by definition, the only choice you could have made. It’s impossible to concoct a situation where you could rewind the clock and choose to act differently according to the exact same set of inputs.

That’s about all I’m going to say in terms of explaining determinism. If you’re not already familiar with the concept then it can be a little bit difficult to unpack, and other thinkers have already done a much better job than I ever could at laying out the basics. If you’re still a skeptic, I would recommend checking out one of Sam Harris’ lectures on Youtube, he dives pretty deep into the common objections people raise. But for the purposes of this chapter I’m going to accept determinism as a basic premise and then go from there. I don’t think you can justify a belief in free will without appeals to God or the experience of agency. And as I already mentioned, the illusion of free will can exist without mapping on to neurological reality. I think any scientifically-minded, intellectually-honest person will have a tough time arguing against this basic principle. The laws of the universe leave no room for individual agency. At the atomic level, everything is simply a great big physics equation unfolding. All of your thoughts and actions are beholden to forces outside of your conscious control. In fact, the notion of acting “freely”—that is, independent of external causes—actually becomes unintelligible. What would it mean to act without causal motivation for doing so? If your actions were random rather than reactionary, would that actually make them any more meaningful? I don’t think so.

Sam Harris, outside of being a notable atheist, determinist, and neurologist, is also very interested in consciousness, spirituality, and meditation. His entire book, “Waking Up” is about how people can have spiritual experiences without religion, mainly though experimentation with meditation or psychedelics. If you spend some time studying Eastern religions, you will start to see the connections between these ideas. Personally, I am a big fan of Baba Ram Dass and his book, “Be Here Now”. Ram Dass, previously known as Richard Alpert, was a professor of psychology at Harvard University in the 1960s, and he participated in much of the early experimental research with psychedelics. His fascination by, and craving for, the sorts of spiritual experiences induced by psychedelics eventually drove him East, to India. In the Himalayas he found a Hindu guru who gave him his new name, Ram Dass, and eventually he brought the lessons he learned back West. But the philosophy he describes goes beyond just Hinduism. It invokes Zen Buddhism, Daoism, Sufism, and even Christianity, demonstrating how different aspects of all sorts of faiths can speak to the same underlying systems of understanding.

One key message that is especially emphasized in Eastern traditions is the idea that you are an entirely determined being. If you could zoom out, and see your life from a God’s eye view, you would see that you are propelled by the universe in a certain direction, like a moth to a flame. Certain drives and pulls will act upon you throughout your life in often unexpected ways. And although this process is inevitable, it cannot be forced. It is impossible to expedite the process, or jump ahead from where you are currently situated. Like a caterpillar turning into a butterfly, or a snake shedding its skin, everything must happen in its own time. There is work to be done, and lessons to be learned. An ethical insight that is unique to this determinist framework is that it offers eternal patience and forgiveness. There is a recognition of the fact that people act the way they do because of events outside of their conscious control. Therefore we should exercise empathy and compassion, seeking to understand the circumstances which brought about a person’s behaviour, rather than antagonize or chastise them for it.

Of course, the idea of determinism exists in Christianity too in the form of predestination, but they are a little bit different. Western, Abrahamic, monotheistic religions tend to view God as a great, omniscient, omnipotent creator, invoking the image of some sentient being up in the sky who is calling the shots and pulling the strings. But this doesn’t carry over to the same extent in Eastern schools of thought, where God is conceptualized as a causal, creative force that can be found in everything, rather than existing outside of the material realm. There is an emphasis on holism over dualism, with a focus on how everything in life is interconnected and interrelated. Therefore there is no meaningful distinction between you and the rest of the world. You are simply operating in harmony as part of a larger, broader system. This makes sense from a complexity point of view, you can conceptualize the entire universe as one great pattern that is unfolding and interacting with itself. In fact, the goal of enlightenment is to transcend dualism—Zen Buddhism is holism to its logical extreme. Its central claim is that the world cannot be divided, all boundaries and differences are an illusion. If you’ve taken psychedelics before then you may have experienced the profound feelings of oneness and universal harmony that these philosophies describe. Similar states of consciousness can be achieved in total sobriety, they are simply more elusive.

The ethical takeaway here is that not only are our lives entirely predetermined, but they are also deeply interconnected. The actions you take are like the flapping of a butterfly’s wings, they have consequences which ripple out into the world in ways far greater than you could possibly imagine. This is where the concept of karma comes from, or the biblical notion that you reap what you sow. What you put out into the world has a way of coming back to you. I don’t mean this on a conceptual level, but a literal one. The patterns of causality are sewn into the very fabric of reality, it is impossible to extricate yourself from the environment you find yourself. We are all connected, for better or for worse, and we can only move as fast as we all move. It is impossible to “get ahead” and exist in an ideal bubble isolated from the rest of reality. The ethical implications of this have clearly communitarian values. What is good for others is also good for you and vice versa, it all feeds back into the same system.

The final aspect of Easternism I want to touch upon is ego. You may have heard people describe the phenomenon of “ego death” that results from deep meditation or taking psychedelics. This refers to the state of consciousness that arises once one has lost all attachments and sense of self. All the stories you tell yourself about who you are and what it is you think or want. This shift in awareness allows one to be completely content in the present moment, without any concern for past or future predicament. Many philosophers have observed that the reason children are so happy is because they constantly exist in this state of being. They aren’t worried about what they did last week or what happens tomorrow, and they aren’t seeking external validation from the world in the same way adults do. Grown ups walk around with funny ideas in their heads about needing a new raise, new car, or new house and then being happy, rather than realizing that they can be content with the world as it is right now. Eastern philosophy suggests that desires themselves are what lead to unhappiness; the moment a given goal is achieved, a new one must replace it. The idea is that constantly wanting rather than being is what produces so much psychological stress and dissatisfaction.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. It is possible to detach from your experience of ego. While you may have been formed by a certain set of experiences, you are by no means beholden to them. Your sense of self is, to some extent, an illusion. The notion of an “I” who has certain inalienable qualities and characteristics, only has as much stock as you put in it. And it is possible to have awareness without attachment. For instance, the unpleasantness of being too hot or cold will only be amplified the more attention you pay to it. However with practice you can learn to experience undesirable states of being without the subsequent emotional suffering. David Blaine is a great Western example of this, having done many extreme feats of physical endurance and suffering minimal adverse effects. Subjecting himself to extreme periods of pain, sleep deprivation, starvation, asphyxiation, and much else. In the East, there are stories of monks who spend their entire lives training to withstand intense fasts, temperatures, and physical forces that would be otherwise impossible and seem superhuman.

So, how is it possible? Well, this brings us back to the beginning of the chapter and the idea of practicing awareness without attachment, otherwise known as meditation. Learning to notice your thoughts, feelings, and emotions as something that exist outside of and separate from yourself. This practice has many practical uses that can be applied to daily life as well. As we saw in the forest, focusing on the world around you can be used to prevent panic attacks as well as other states of psychological duress. Sam likes to use the example of road rage; instead of existing in an angry, irritable state as a response to a situation you have no control over, you can simply go up one level of awareness and watch as the emotions pass through you. But you don’t have to be in the emotions, it is possible to observe them without attachment. The same principle applies to pain, or discomfort. There is always a deep, calm, consistent centre that you can learn to access regardless of circumstance.

The best example I have encountered for practicing mindfulness comes from Duncan Trussel’s mother, in his Netflix show Midnight Gospel. She describes getting present as a practice that is available to anyone, at any time. Even if you have nothing else, you can always get present in yourself. I encourage you to try it now. Close your eyes and slowly shift your focus to the feeling of your body. See if you can sense the inside of your hand, that feeling that exists under your skin. What is it like? Warm? Numb? A little tingly? Now, gently let your attention go up your arm. See if you can sense your arm from the inside, fingertip to armpit. Take your time… What about both arms at the same time? Can you feel your hands and elbows simultaneously? Now add in your legs, focusing purely on the feeling of your body. It’s not easy to do! It requires conscious, controlled effort. You must pull your awareness away from your mind and into your body. The next thing you can do, while still sensing your hands, arms, and legs, is to listen. Keep your eyes closed, and your body in focus, and just let the world come to you. What do you hear…?

Part #3. The Croak and Call

*Ribbit*

The sound startles you to your senses. You peel open your eyes to spot a frog sitting by the brook on a large rock a few feet in front of you. Staring straight into your eyes, it raises a non existent eyebrow.

“You gonna sit around all day or what?” He asks.

“I’m meditating,” you reply.

“Well, you’ve been sitting there for hours now. Don’t you wanna explore a little? Come on kid, you’re in Wonderland. This is a once in a lifetime opportunity!”

“I don’t need anything though,” you say. “I’m happy to just sit here and let the world wash over me. It’s quite liberating in fact, you should try it.”

“I don’t get you humans. What’s the point in all that freedom if you’re not using it for anything?”

“Well that’s just it, see? I’m not free. Anything I could wish or want or do is just a product of a long chain of events that came before me. So long as I’m not free I’d rather not delude myself into thinking otherwise. So I’ll just sit here, thanks, and wait until I get a sign from the universe that I should be doing something different.”

The frog clears his throat, “downstream from here is a little village that is being harassed by a dragon. They need a hero to come and slay it.”

“That’s nice,” you say. “I hope one comes soon,” and you return to your breathing exercises.

“Look bucko, wasn’t the whole reason for coming to Wonderland the fact that you wanted to go on an adventure? Where’s the fun in doing nothing?”

“Desire begets desire,” you say. You’re pleased with yourself, it sounds like some ancient Buddhist wisdom. “It’s true, I may have come here looking for adventure, but in the process I learned something much more meaningful. I am not really here at all. All I am is a bunch of attachments. Lose your attachments and you lose yourself, and then you can just be. No need for anything else. I’ll forgive you for not understanding me, everyone learns in their own time, you can’t help it.”

“You realize you haven’t actually freed yourself from anything, right?” Says the frog. “Your desires have simply turned into a desire for no desires. Nothing’s actually changed. You’re still stuck in that same deterministic loop that brought you here. You cant escape it by not doing anything, because doing nothing is still doing something.”

“Well, what do you think I should do?” You snap.

“What I think both doesn’t matter, and matters more than anything,” says the frog.

“How do you mean?” Now he’s got you interested.

“Well you’re right about determinism. I don’t have control over my actions any more than—” he pauses to catch a fly out of the air. “—you do. But what you do also depends on what you have decided to do, and the whole world feeds those decisions. So I wont blame you for accepting determinism any more than you would blame me for not doing so. It’s all a matter of perspective, see?”

“I’m confused,” you say.

“Well look here. Let’s pretend you forgot about all this determinism nonsense for a moment and I told you that the world is your oyster and you can do anything you want, what would you do?”

“Why I... I would go slay that dragon!”

“So then, why don’t you?”

“Because I’m not a hero. And like I said, I don’t actually have any control over what I do. Things just happen to me and then I react the only way I know how. So I guess if some wizard popped out of nowhere and trained me to be a dragon slayer then I could fight it. But I don’t think that’s going to happen. Unless you…?”

“Oh no, I’m just a regular old frog. You can give me a kiss to make sure if you like, but I wont be training you in dragon slaying anytime soon.”

“So then what’s the use?” You lament.

“What’s the use indeed. What is useful to you? If you want to go on an adventure then the only thing stopping you is yourself. But so long as you choose to get in your own way you wont be going anywhere”

“I feel like we are talking in circles, what control do I have over getting in my own way or not?”

“Total control, you just have to decide if you want it or not. Look, bucko, you’re right, your life has been absolutely determined right up until this very moment. But just like all that spirituality suggests, there is something special about the here and now. It’s true, you are an effect, but you also have the capacity to cause. Your consciousness exists to contend with potential and make choices. But what you ultimately choose to do depends entirely upon what you believe you can do. Limit your scope and you limit your potential, but broaden your appetite and who knows what you could be capable of. As my father always told me, you miss 100% of the flies you don’t stick your tongue out at.”

“So… You’re saying I should eat flies?”

“I’m saying that beliefs beget outcomes. Causality doesn’t just work in one direction, but two. And the future will unfold in accordance with whatever you set your mind to. So be careful with what you set your sights upon. Your attention and your aim are your most valuable assets, and you will only see what you have decided to look for. Forget forgetting desire, it doesn’t need to be a detriment. Cast aside desire for desires sake, but make no mistake, desire can also be a pull, and pursuing that pull is what makes life meaningful. How else do you think a salmon makes the daring journey upstream? Or a man mounts the courage to dream a dream? If you want to change the world, you can. But first, you must change your mind.”

You consider this for a moment. “You said the village was downstream from here, right?”

The frog nods. “Are you reconsidering slaying that dragon?”

“Well, I’m not making any promises, but I’ll see what I can do,” you say, getting up from your spot by the stream.

“With that attitude, you can do anything,” replies the frog with a wink, sticking out his tongue to gobble up a nearby caterpillar.

Part #4. Just do it, Jesus Christ, Jordan Peterson

Okay, so I’m trying to make a slippery argument. Ultimately, I am a determinist. I believe that our consciousness allows us to contend with potential and make choices, but whatever we choose to do is ultimately the only thing we could have done in that circumstance. The same inputs will always produce the same outcome. That being said, inputs matter! And philosophical frameworks that emphasize our ability to make choices will cause better choices to be made. There is this weird interaction that occurs between expectation and reality. What you believe, becomes. A “can do” attitude has very real consequences. People benefit from philosophies that emphasize their capacity to make tough choices, to persevere, to pull themselves up by their own bootstraps. This idiom is intentionally paradoxical, it implies getting support or motivation from within, which is really what the concept of “free will” seeks to share. The idea that you can move yourself by your own volition, without needing an external cause. The paradox comes into play when you realize that this is possible, but only to the extent that you believe it be so.

I’m sure we’ve all experienced this first thing in the morning, torn between the comfort of your bed and getting up to start the day. If you lie there thinking, “oh, just five more minutes!” then you are almost certainly going to doze off again. But, if instead you tell yourself, “okay, on the count of three I’m going to get up. 1, 2, 3!” Then, surprise surprise, you’re much more likely to get up and start your day. This may sound painfully obvious, but it really matters. All life is is a series of decisions made moment by moment. Whatever story you tell yourself about what you are capable of doing is almost certainly going to come true. Within reason, of course. I’m not suggesting that a philosophy of mind over matter is going to allow you to lift cars or win a hot dog eating contest, but it might encourage you to run an extra mile you didn’t think you had in you. The motivational power of Nike’s “Just do it” slogan fits in nicely into this framework. When working out and on the brink of exhaustion, if you tell yourself, “I have to stop”… well, then you will. But, if you can train your mind to say “keep going,” then you will find the courage you need to continue. It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. And people benefit from philosophies which recognize this feedback loop.

This is one of the primary distinctions between Eastern and Western religions. While Eastern schools of thought emphasize determinism and a more holistic approach, Western religions favour dualism and the notion of a nonmaterial soul. Why would this be the case? Well, if your soul is something special that was given by God, then this would allow you to act independent from the material, causal world, creating the concept of free will that most of us are familiar with. Now, I’m not going to spend any time arguing against the existence of God. We live in a more secular society than ever, and far more people are losing their faith every day than gaining it. The advances and explanations we have gained through science are just too overwhelming. When we have real answers to some of life's biggest questions, we don’t need narrative ones. Except, maybe, on this crucial issue. Materialism is destined towards determinism, and that can seem quite depressing if you are unaware of the interaction between expectations and outcomes I laid out earlier. This is why I believe so many stories emphasize the power of the individual to overcome hardship and make meaningful changes in the world. These ideas are true, but they must be believed in order to be acted out. However this does not mean that they must adopt a religious character, they can still be communicated and understood in atheist terms.

For instance, take sayings like, “God works in mysterious ways,” or, “when he closes a door he opens a window.” These are valuable framing tools, they encourage people to see setbacks as potential opportunities rather than obstacles and stay optimistic in light of bad circumstances. You can rationally understand how beliefs like these would bring about beneficial outcomes without needing to invoke a literal conception of God as playing some crucial role. “God” is being used as a metaphorical stand-in for the universe getting in between you and your goals. And your interpretation of events like these matters! If you lose your job, or your partner leaves you, these can be difficult circumstances to overcome. But an attitude that encourages you to believe that the universe is on your side will help you make the best of a bad situation. Oftentimes some of the worst moments in our lives can lead to some of the best, and we can only see the way different causal forces influenced that after the fact. Looking back on your life I am sure you can recognize certain crucial tipping points that changed things in dramatic ways while seeming negative or insignificant at the time. We have all wondered, “if only that hadn’t happened, where would I be?” There is an implicit understanding of determinism in our lived experiences, we just generally fail to apply the same principle to the present moment.

There is a unique insight from Eastern philosophies that I want to draw your attention to: there is something special and sacred about the present moment. Your ability to make decisions is active, not passive. And you don’t need to listen to the story you tell yourself about who you are, your past need not define your future. You can always choose to change yourself, to act differently, to be better. This process may be difficult, yes, but it is never impossible. This idea is highlighted by a classic narrative trope, where at the climax of a story the hero offers the villain a chance to change their ways. There is some choice that must be made that will either seal their fate as the bad guy, or offer an opportunity for redemption. The choice that the villain ultimately makes will depend on how committed they are to their villainy. If they do not want to change, or do not believe it is possible, then they will double down on their commitment to evil and become irredeemable. But maybe the hero says something crucial to them that allows them to think differently and believe that they can change, that makes them want to change. You can take this idea out of the fictional realm and apply the same principle to reformed criminals. Decisions always depend upon the stories you tell yourself about who you are and what you are capable of.

Ultimately, I believe that this is why Jordan Peterson defends religion: he recognizes that narrative power outweighs the material facts of reality, and he sees the Christian ethic as championing the causal power of the individual. This is why so much of his advice focuses on the adoption of responsibility. You must get your life straight and align your speech, thought, and action to be oriented towards the highest good you can conceive of, taking on the greatest load you can bear. And this is hard work! It requires conscious effort and exertion. Lots of people avoid doing what they know they should be doing for precisely this reason. It is much easier to do nothing and comfort yourself by the deterministic notion that you couldn’t possibly be doing anything else. But this brings about a sense of guilt and shame, since we all know that there is some good we could be doing which we are actively avoiding, and the consequences of that lack of action are unfathomable. Who knows how good the world could be if we were all doing what we knew we should be doing? Avoiding responsibility is bad for your psychology, whereas voluntarily adopting it produces the best outcomes for society as well as individuals.

So, what’s the problem with Peterson’s approach? Well, when asked during a debate whether he believes God exists, he said something interesting. “I act as if God exists.” Now, this is Jordan’s downfall. His entire belief system relies upon what I like to call a noble lie. His philosophy follows the tradition of Plato, not Aristotle, as he believes that morality cannot stand on material, rationalist grounds alone. He needs religion as a crutch to support his central claim: that Man has free will. A proposition that he believes to be self evident because of subjective experience, without any objective support. The problem with this approach is that it isn’t converting anyone. Although I ultimately agree with his conclusions in the moral realm, they are the consequence of a lie that lies at the centre of his ethic. He can’t convince any atheist to support his cause without appealing to God, and it seems to me like he doesn’t truly understand the issues people take with his arguments. He, as well as other conservative thinkers like Ben Shapiro, rely upon a religious notion of free will in order to support their ideas. But you can’t preach bootstrapping to an audience that believes in determinism, and blaming poor people for their problems makes you sound insensitive and arrogant, not intelligent. It’s mystified me for many years why these thinkers don’t recognize the flaws that a reliance upon religion brings to their arguments, or why they are incapable of understanding what Sam Harris means when he talks about determinism. Sam, on the other hand, fails to integrate his position persuasively, so that’s what I’m going to try to do now.

Trust me when I say that I have scoured the internet for sources of Peterson talking about free will and determinism, and, to my astonishment, he consistently overlooks or misrepresents the central claim that is being made. He seems to side-step the issue by insisting that people have the capacity to make choices and that is what gives them free will, while overlooking the fact that the ultimate choice which is made is determined by a preexisting set of inputs, which is what a determinist is arguing. Sam, although I love him dearly, astonishes me by his failure to twist the knife in on this precise point, or point out the fact that Peterson’s entire career hinges upon implicit determinism. It’s somewhat ironic given the fact that Jordan will frequently discuss being incredibly moved by fans coming up to him and explaining that their lives were in a really bad place until they encountered one of his lectures. Without being presented with compelling ideas as to how they can exert meaningful control over their lives, people will fail to do so. You can’t blame a kid for having a messy room if he never had a good influence telling him the value in cleaning it up. And you can’t expect people to discover those ideas purely by their own volition, they need to be exposed to them first. Some people may be able to arrive at such philosophical conclusions through first principles, but you can’t expect that of the average person born into unfortunate circumstances. Again, an ethic of bootstrapping begets bootstrapping, whereas an environment that emphasizes determinism without agency leads to depression and degeneracy.

In fact, the entire notion of personal responsibility hinges on the reality that your actions have a direct impact on the lives of other people. If people are truly free agents, then what I do should have no social consequences outside of myself. I could walk around sneering at bus drivers, not tipping my server, and refusing to call my grandmother without those actions negatively affecting anyone else. But clearly, this is not the case. Rather, it is precisely because the world is deterministic and our lives are so interconnected that an individual’s actions matter so much. Although they may seem like small transgressions, these things add up. If you want to live in a happier, more positive world it is your job to go about creating it. Of course, as a server myself, if someone doesn’t tip me I try not to take it personally. But if you’ve ever been complimented by a stranger passing you by on the street, or had the car ahead of you pay for your drink at the drive through, then you will know how much difference a small act of kindness can make in brightening your day. These are small examples, but the stakes can be astronomical. Who knows who may be reading this that could be influenced to make a different decision based on the ideas discussed here? How many people will that decision impact? And who will they impact in turn? It’s all connected, it’s all a great big feedback loop. I was shocked when reading The Moral Landscape to discover that determinism wasn’t central to Sam Harris’s thesis. So this essay is my attempt at advancing the arguments I wished he had put forward.

Ultimately, I am a determinist. I think science makes that abundantly clear and I don’t have any religious allegiances that would make me think otherwise. However, just because the world is deterministic does not mean that you are not capable of making meaningful choices, and the ideas that you accept regarding what you are capable of will have a direct impact on whatever it is you ultimately do. Thus, a culture that emphasizes agency and the causal power of the individual is also of central importance. These ideas don’t contradict each other, they amplify one another. The world is deeply interconnected. This means that you have the capacity to both cause, and to be caused. Reality will manifest in accordance with whatever tendency you lean into. But you don’t need God to justify this belief, it is a logical consequence of the nature of the universe. Our ethical intuitions or value orientations don’t rely upon fictions or stories, they are a product of the world exactly as it is. You can’t control other people, therefore you should be empathetic, and attempt to understand them. You might be able to persuade them of something, but only if you listen to where they are coming from and are willing to exercise patience and forgiveness. On the flip side, you are entirely in control over your actions, so you should hold yourself to a high standard. Not an impossible one (the laws of determinism apply to you too), but an ambitious one. You should strive to work hard and pursue what is meaningful to you, adopting the maximum responsibility you can bear. Why? Because the higher you aim the more you will achieve. The world reveals itself to you in accordance with your expectations. Beliefs beget outcomes.

That’s my take on ethics, broadly speaking. They may be a little unconventional, but I think this approach is crucial for the rest of our moral and political reasoning. We have to have a philosophical framework that allows us to make sense of free will and determinism simultaneously. All I’ve tried to demonstrate in this chapter is that you are able to exert conscious control over your actions, and hopefully that understanding will promote you to make better choices in the future. But what goals should we be aspiring towards? Sure, I can make choices, but what should I choose? What values and ideals should motivate my decision making procedures? Well, I’ll explore that in the next chapter. If ethics is concerned with interpersonal values, then consider morality to be how those values manifest on an individual level. This chapter was the “why”, next I’ll be tackling the “how” and diving into individualism, objectivism, and the hero’s journey.

Continue to Part 5: Hero: Moral Ego

Wonderland is a free publication that outlines a philosophy and political vision for the 22nd century. To support my work and receive updates on new posts, sign up for a free or paid subscription.

Share this post