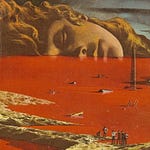

This is the chapter where we tackle morality. Now, I want to make a distinction here between morality and ethics, which is what was discussed in the previous instalment. To me, ethics is concerned with universal principles of human behaviour and how they come to emerge out of reality, whereas morality is concerned with what you should do specifically. This constitutes right and wrong behaviour on an individual level, so it has a strong psychological component. In my opinion, the right moral approach promotes better outcomes both in life, and also mental and emotional wellbeing. Morality is like the glue, the how and why which give your actions coherence, meaning and purpose. Without an integrated moral framework, you are lost and unsure, unmotivated and undisciplined, and you will experience a sense of fear and guilt that cannot be explained or gotten rid of. Even if you have a belief system that you adhere to, it is useless if you are not sure why you are committed to it. This is why I don’t think religious prescriptions are a proper substitute for moral philosophy. They may tell you what to do, but not why it is you are doing it. Whereas if you have a why, then the what will come naturally. This chapter is going to be discussing reason, individualism, and heroism. I’m pulling ideas from Jordan Peterson, Zen Buddhism and Stoicism, while introducing Objectivism as a key player. Now, let’s pick up from where we left off in Wonderland…

Part #1. The Gate

You’ve arrived at the town. Well, the gate at least. The city is surrounded by a large, tall, stone wall. But in front of you is a green door with bronze trim, with a sign that says, “knock if you want to come in”. You give the knocker a rap, and within a snap there’s a man in front of you with a bushy moustache and a grin.

“Hi, hello, how do you do? The name’s Tru, how can I help you?”

“Um, hi,” you say, a bit unsure. “I’m here to slay the dragon.”

“Wow! That’s fantastic news to say the least! Tell me, how do you plan on slaying the beast?”

“Um, good question. I haven’t thought about that yet. I thought maybe I could come inside and…”

“Come inside?” The guard gives you a confused look. “Why would you want to come inside? The dragon is out there, not in here!”

“Yes, well, you see, I don’t actually know where the dragon is or how to slay it. I was hoping that there would be a wizard or something here who would… you know… tell me what to do?”

Tru looks at you. “Why would you show up offering to slay a dragon when you don’t know the first thing about dragon slaying?”

“I… I don’t know! Isn’t that what I’m supposed to do?”

“Says who?” Asks Tru.

“Well, I… I met this frog and he told me that your town needed a hero so I—”

“Oh, so you’re some sort of hero?”

“Well, no. Not yet, but I want to become one!”

“And how’s slaying a dragon gonna help you do that?”

“Well, that’s what heroes do, isn’t it?”

“Oh no, you’ve got your cause mixed up with your effect. Some heroes slay dragons, sure. But simply slaying a dragon doesn’t make you a hero, it just makes you a dragon slayer.”

“But… I’d be helping your town. That’s heroic! …Isn’t it?”

Tru scoffs. “What’s so heroic about risking life and limb to help a town you’ve never even been to before? Why should you want to help us? Do you even know where you are?”

“Um…”

“Yes! The town of UM, that's where you’ve come.”

“The… town of UM? That’s dumb. I mean… What’s it from?”

“UM as in the opposite of Mu.”

“Mu who?”

“Haven’t you heard? It’s from a koan by Joshu”

“What’s a koan do?”

“Oh, I see,” says Tru, “you haven’t a clue. Koans are little riddles which are used to provoke enlightenment. A monk once asked Joshu, “does a dog have Buddha nature?” Joshu answered, “Mu”. In doing so, he unasked the question, rendering it moot, if you will. Contrarily, it is our tradition, in the town of UM, to ask the very question you didn’t know you had raised.”

“Why?” you ask.

“Now you get the picture!” Says the guard with a grin.

“I’m confused… Can’t you just let me in?”

“I’m sorry sly, but I can’t let you in until you know why.”

“I—why not?”

“Nice shot,” says Tru. “But that wont do. Like I said, good reason only. That’s our gold standard.”

“But it took me all day to get here! And I’m tired and hungry. Isn’t that good reason enough?”

“And yet you haven’t enough reason to find yourself some food? I’m sorry, but the town of UM wont help anyone who isn’t first willing help themselves. And besides, you’re a young adventurer in tiptop shape! You’ll be alright for the night.”

“So you’re gonna make me sleep outside?!”

“Me? I’m not making you do anything. You can do whatever you like. But you better think fast, it’s getting late!” Says the guard as he closes the gate.

“Wait!” you cry, banging at the door. But Tru answers no more.

Part #2. Good Reason

Let’s talk about reason. This word has two meanings, which are often related but don’t always overlap. “Reason” can refer to both casual explanations and justifications as well as rational thought. But “rational” too carries the same issue, as it can mean both “rationale”, as in a reason for doing something, as well as “rational” in the typical, logical sense we are familiar with. It’s entirely possible to do things which are unreasonable or irrational while still having an identifiable reason or rationale for doing so. For instance, if I’m angry at someone and I hit them in the face, clearly this action is not very reasonable—it is emotionally motivated and makes matters worse rather than better. But at the same time, you can easily understand the reason why an angry person would want to hit someone in the face—they want to hurt them. In which case, mission accomplished. In fact, if your goal is to hurt someone and you hit them in the face, then that action is entirely rational. You wanted to create an output (their pain) and you provided the correct input (your fist). Your motives may be questionable, but the action itself is perfectly logical given your intent.

Determinism implies that people are rational actors, in the causal sense. Whatever you ultimately do is the only thing you could have done in that circumstance. But this by no means suggests that people will always do what is rational, as in most optimal. Clearly our perceptions and judgements are fallible; we are more than capable of making mistakes. Our emotions, expectations, and experiences all play a meaningful role in shaping our behaviour. But people will always do what they think is best in a given situation. Of course, hindsight is 20/20 and we might very well regret a decision after the fact. However, at the time, your actions will always be in accordance with your available knowledge and beliefs.

So there are three factors that motivate your decision-making mechanism: what you want, why you want it, and what you believe you need to do in order to achieve it. Let’s say you’ve gone to buy a car. This is the want. You talk to the dealer about your budget and needs, and he provides you with three options. One is affordable, one is environmentally conscientious, and one looks really cool. Which car is the most rational purchase? Well, it depends on why you want it, doesn’t it? The cheap one saves you money, the clean one saves the earth, and the cool one might just save your sex life. You’ll buy whatever car you believe will fulfill your goals. But there’s a catch—it may turn out that the cheap car costs more to maintain than one of the more expensive models, and you end up paying more in the long run. Or maybe the electric car actually produces more greenhouse gases than the gas guzzler. Or perhaps the girl you’re looking to impress cares less about flashy sports cars than you thought she would. All of these things are possible, and yet none of them would make your decision at the point of purchase any less rational.

My point is that you will never knowingly make a decision that produces an undesirable outcome. What constitutes “undesirable” depends on the disposition of the individual. An addict may be able to logically recognize the issues with their addiction while still rationalizing a reason to continue their abuse. They are simply acting in their short term self interest rather than long term. There’s nothing unreasonable about doing things you know you shouldn’t be doing if other incentives exist. For the addict, the undesirable outcome they want to avoid is staying sober. Why this is the case will depend on the individual. Maybe addiction runs in their family, maybe they’re depressed, maybe they’ve surrounded themselves by bad influences, maybe they just don’t care. But there is always an identifiable motive, either implicit or explicit.

I remember once hearing Sam Harris say that he experiences a sense of uncertainty or randomness when making decisions. This surprised me since I couldn’t disagree more. I very strongly feel that there is an internal logic and structure which guides my actions. I treat my life like a game of chess, with certain goals I want to achieve and certain moves I need to make in order to achieve them. I’m always thinking a few steps ahead, I always have contingency plans. If at any point someone was to stop me and say, “hey, why did you do that?” I could reply in an instant. Maybe it’s because I’m highly introspective, but to me the motives for my behaviour have always been entirely transparent. I don’t feel as though I act freely, I act rationally. I can always identify what causes are motivating my behaviour, both in terms of what I want and why I want it. The “why” is what I want to attend to this episode. What constitutes good reason?

Of course, this question begs another: are some reasons better than others? To which I say: yes, absolutely. I don’t buy into moral relativism. I view moral philosophy as a tool that allows you to move through life successfully. It is a code of values or principles that guides how you interpret and act in the world. In order to be effective, it must speak to something real about the nature of reality and your relationship to it. So, by definition some answers must be better than others. Morality is a consequence of consciousness and agency. If we were able to survive on instinct alone then there would be no need for moral reasoning. But the fact that we are capable of making choices means we need some standard through which to choose. These motives can either be consciously adopted or haphazardly accumulated.

My argument is that rationality and morality are the same thing. Having “good reason” means you’ve thought things through. Your wants are not based on whims but whys, and those whys are wise. They have been carefully selected by considering both context and consequence. Reason is therefore the core value. Everything else follows from this. Why? Because you asked that question. If I tell you, “I value this,” and you ask me why, my answer is appealing to a higher value, isn’t it? It’s “whys” all the way down. Now, there may be lots of other values I hold dear. For instance I think people should exercise honesty and forgiveness… but there are also always going to be situations where I would tell a lie or refuse to forgive someone. And in those circumstances I would have good reason for doing so. Explanation is everything, but it must have a referent that is real. It must be tethered to reality in some meaningful way, otherwise it’s unintelligible.

Because of this, convictions without reasons will work until challenged. Many people go through life wanting and believing things without ever introspecting as to why. Or, they settle on some surface level explanation rather than digging to the core. I would never fault anyone for this—you can’t expect everyone to become first principle philosophers—but it does create problems for a society that has found its foundations in bad moral premises. Religious orthodoxies, for instance. The “whys” in that circumstance bottom out at God. Now, there might be lots of good stuff in the middle that has some value, but if the foundations are rotting, then how do you expect the structure to survive? That’s why I prefer a morality that is based in reality. So long as we experience existence, we will share a referent that provides a groundwork for explanation.

So, I’ve smuggled a little premise along with me: since people are rational—there are reasons for their behaviours and beliefs—this means that they can be reasoned with. You just have to identify where and why you disagree. Of course, some matters are entirely subjective… I’m not for a second suggesting that you can use logic to persuade a chocolate ice cream lover than vanilla is superior. And some people are closed minded; they have found a position that they are comfortable with and don’t want to question it any further. Don’t waste any time trying to convince someone who refuses to think. But for those who remain open minded, as I hope you are, they can be persuaded. Once you understand the rationale, or the value, in adopting a certain point of view it becomes easier to adopt. This entire section is a funny little paradox which folds in on itself as I am essentially trying to convince you of the value of reason by appealing to your reason. Most people reject rationality because they believe it contradicts morality in some fundamental way. What I’ve tried to demonstrate is that the exact opposite in true—they operate in harmony. To be moral is to be rational. Any other conception of morality denies reality. How can you make claims about how a person ought to live in the world without first acknowledging the fact that you are dealing with a living person? This premise carries with it a collection of corollaries which must also be considered.

Part #3. The Woods

The gate clangs shut and you turn towards the woods. You realize that for the first time since you entered Wonderland you earnestly have no clue what to do. Everything up until this point was a consequence of the events which came before it. You found your way out of the maze and into the forest where you followed the ants and met Aunt Hillary who induced a fugue and caused you to flee towards the stream where you found the frog who sent you to meet Tru. You didn’t have to think about what you were going to do next, things just kept happening. Now, you are alone with nothing but the setting sun and an empty stomach. You suddenly recall that you’ve been in this situation before, in the maze, and you learned your lesson then; there’s no use sitting around when you’ve got a problem to solve. So, you set out into the woods once again. But this time, you’re not wandering aimlessly—your eyes are alert and your head is on a swivel. You’re looking for food.

It doesn’t take long before you find a bush with some berries which look promising… but what if they’re poisonous? You look around and on the ground notice a few discarded seeds. Then you spot a squirrel who is happily harvesting some of the fruit. You assume this means it must be safe to eat. You help yourself to a few—and they don’t taste half-bad—but the bush is nearly picked clean, and you know this wont be nearly enough. Then you remember the stream. You can’t recall the way you came, but you listen for the sound of running water until you find your way back again. You walk downstream, searching for signs of fish. Eventually you reach a spot where the water is deep enough that you find a few swimming below. How will you catch one though? You try to snatch one with your hands, but they’re too quick. You realize you’ll need a spear, or a stick. You spend a few minutes foraging in the forest and find a few options, but none of the branches are sharp enough. If only you had a knife, or—oh, a stone. You look around the stream for a sharp rock, but they’ve all been made smooth by the current. If only there was one that weren't! Wait, what if you… you grab a stone and proceed to shatter it into smaller and smaller pieces until you produce a side with a sharp edge. Now you can carve yourself a spear. You sharpen up a stick real quick and pretty soon you’ve caught yourself supper. But you’re not done yet. You’ll need a fire, and there’s not a lot of light left.

You swiftly snap your spare sticks into twigs and assemble a stack of stones into a circle, building a little tipi with the branches in the middle. You dart back into the woods to grab some crunchy leaves for kindling. Just in time, it’s nearly dark. Now for the challenge of setting a spark. You consider this for a moment, and take your time selecting two dry sticks you can rub together. You know that it will take a lot of friction to generate enough heat, and once you start you can’t stop without losing all of your progress, so you have to be sure. Once you’re happy with your set up, you begin the process. Within seconds your hands are hot and raw, but you keep going, knowing that each bit of discomfort endured is bringing you closer to a hot meal. Within a few minutes you start to see smoke, and then the kindling catches and suddenly you have a campfire. You take a moment to beam at your creation, and even though it’s just a measly little fire, you can’t remember a time you’ve felt more accomplished. You skewer your fish and roast it up nice and crisp and by the time you’re tucking in, you swear it’s the best thing you’ve ever tasted. You fall asleep by the fire feeling warm, full, and proud.

Part #4. Personal Purpose

Morality is the realm of philosophy which is concerned with how a person ought to live. This carries with it some implications—“living” is a key word here. In order to live you must survive, but Man cannot survive by any means alone. Some actions will bring you closer to death and some will bring you further away from it. Unlike other animals, we don’t come preloaded with instincts telling us how to find food or create shelter. Our actions are not automatic, they must be consciously considered. This means we are capable of making choices which can both help and hinder us. The standard you use to discriminate which is which is what morality is all about. So what reason should guide your actions? Well, your own livelihood is a good place to start. A moral code of conduct that causes man to suffer and die rather than to prosper and live is malevolence in masquerade.

So how does one survive? This is the problem you faced in the woods, and the solution is based on a principle you discovered back in the maze: you must use your own senses and mind, for they are the only tools available to you. So what did you do? You walked into the woods and searched for food. Your eyes honed in on the red berries—our monkey brains are good at things like that—and then you used your mind to determine that they were safe to eat. The same thing happened with the stream: you thought of fishing and then listened for the sound of rushing water to guide you to where you needed to go. You had to solve problems, smashing rocks and sharpening a spear and forging a fire, and the entire time you acted with good reason. Your actions were logical and methodical, purposeful. Every step of the way brought you closer to your goal. This is the moral ideal. You identified a purpose and used your reason to achieve it. In doing so, you experienced pleasure and pride, for you know you did the right thing.

The purpose of your life can be defined by no one but yourself. This is for the same reason that you must rely upon your own senses and mind to navigate the world. No one else shares your subjective experience. No two mazes, or lives, are alike. They may be shaped by the same metaphysics, but their specific manifestations are as diverse as the individuals who occupy them. How could anyone else be a better authority on what you should do with your life? They may be able to persuade you by appealing to your reason, but ultimately your own mind must be the final arbiter. Otherwise you are acting without good reason for doing so.

Now, lots of people wish to evade the responsibility of thinking by surrendering their standard of judgment to some higher authority. They assume that surely society must be smarter than me, a measly individual. And this may sometimes be the case, but it isn’t always. If you remember, in chapter two I talked about how complex systems benefit from variation, if all of the ants in a colony followed the same path they would never discover anything new to eat. The environment isn’t stagnant but constantly changing. In order to survive, we must evolve. And you don’t get evolution without mutation, without difference.

In society, individualism is the manifestation of this same principle. Without free thinkers we would never have any progress. Galileo is a good example of this: just because the entire world believes something doesn’t mean you have to agree if you have good reason not to. Strength may exist in numbers, but knowledge rarely does. Of course, fear is a powerful motivator and many would rather surrender their mind to the the mercy of a mob in order to escape ostracism. But it is precisely when this happens that history goes sour, when individuals become incapable of saying “no” and knowing why they are saying it. Without a code of values, without good reason and purpose guiding your behaviour, you become susceptible to bad actors. We all sneer at the S.S. Officers who said of Auschwitz, “you can’t blame me, I was just following orders.” As if forfeiting the responsibility of thought makes one morally righteous rather than reprehensible. Blame is an infinite regress, no one can be held accountable for your actions but you.

Therefore you must be able to think by and for yourself, independently working to further your own ends, your own purpose. You cannot live your life for anyone else's sake, nor should you expect anyone else to live their life for yours. The world doesn’t owe you anything. This is why the town of UM won’t let you in unless you have good reason to enter. This might feel unfair, but the fact of the matter is outside of your control. Just as you should not try to reason with someone who refuses to think, you cannot attempt to bend reality to your whims. You must work with it, not against it.

Another way of saying this is the old Alcoholics Anonymous adage, “may God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.” This same sentiment can be found in Stoicism, Objectivism, and even Buddhism. It’s a simple fact of life that there is an outer world which exists outside of your conscious control and an inner realm which is entirely your domain. If you focus your energy on wishing you could effect things outside of your causal capacity, you’ll experience nothing but fear and frustration. The secret to cultivating a peaceful, pleasant state of mind is only attending to that which you can do, and doing it.

Ram Dass once said, “I can do nothing for you but work on myself and you can do nothing for me but work on yourself.” What he means by this is that all action stems from the individual. The only way that you can hope to improve the world is by improving the role you play in it. The question you should be asking yourself is not, “what can I do?” as you currently are, but, “what must I do?” meaning, who should you become? In order to truly contend with reality you must be willing to adapt and change, willing to learn, willing to do work.

There’s this funny idea we’ve adopted where we see work as something that should be avoided. Work requires active effort and exertion, it is by-definition something that is not easy to do. But this doesn’t mean it cannot be enjoyable, it depends entirely on your disposition. If you work without purpose, without good reason, then of course you will grow to resent it, for there is no meaningful “why” which makes it all worthwhile. Whereas if you know what it is that you want to achieve then productivity is simply part of the process. Buddhism and Objectivism both recognize how true immersion in one’s work creates total focus and clarity. You enter into a flow state where you are no longer thinking or feeling about what you are doing, you’re simply doing it. You and the work become one. “Being and becoming,” is what I like to call it. Presence that is simultaneously purposeful and productive.

Up until COVID came along I was a waitress, and I can’t tell you how much I miss showing up for work and losing myself in the process. Serving is kind of like dancing, you are constantly moving from one thing to another and need to be thinking five steps ahead, updating your plan as new information comes in. I love it. It’s like a little game trying to figure out how I can do things as efficiently as possible. I have systems for everything, every move I make has been carefully calculated and considered, it’s all been optimized. I see no reason why all forms of work can’t be like this, I don’t care if you’re a janitor, cashier, or computer engineer. There is value in taking pride in your work, in learning to love the process and actively trying to be better at it. Instead of just getting the job done, try getting the job done well. For with proficiency comes play. Like learning an instrument, it may be hard work to master the basics, but once you have those down you can start having fun with it. You have to do the work either way, you may as well learn to enjoy and take pride in the process.

Part #5. The Plan

You’re lying in a sunny field when suddenly you spot a flash of white. You sit up, and realize it’s a rabbit, in a waistcoat, with a pocket-watch. Knowing where this story goes you chase after it, and pretty soon, find yourself tumbling down into Wonderland. The feeling of free-falling startles you to your senses and you wake up on the forest floor with the campfire smouldering next to you. You spend a moment hastily looking around for the white rabbit before you realize your mistake. Of course it’s not going to be here, that was just a dream. But, wait, wasn’t that exact series of events how you wound up in Wonderland in the first place? You’re shocked at how quickly you forgot your life outside of this world. Even though it’s only been a few days it feels like a lifetime. What am I doing here? You wonder. You think back on all that has happened since your arrival, how much you have learned and changed. You’re not the same person you were when you first came to Wonderland. You think differently now. You’re more confident, more self-assured. You have courage in your convictions, you know why you think what you think.

You know that reality must be contended with in order to survive and that it has certain rules which must be obeyed. And you know that you must discover those rules for yourself, using your own senses and mind. You know that the world is complex and causal. But causality works in two directions, belief begets outcomes. The more you believe you are capable of making choices the more choices you can make. But what should you choose? You recall the events of last night. How you went out into the forest with purpose and used your reason to achieve your aims. You were capable. You found food, made tools and fire. You took care of yourself. You solved problems. You didn’t panic like before, you just did what needed to be done and you enjoyed doing it. It felt good.

You get up off of the ground and look around. With your hands on your hips you survey the surrounding forest. Okay, so you’re in Wonderland. You don’t know how or why, but so far so good. So what’s next? What do you want to do? You feel as though you could do anything you set your mind to. Oh, I know, you think. I’ll go talk to Tru. I’ve got an idea on how to get through.

Part #6. Self Esteem

An often overlooked aspect of Objectivism is its very deep commitment to the idea that life is to be enjoyed. The principle that every person’s life is an end in and of itself, with their own happiness as their highest purpose. Along with this comes the premise that life is good. Objectivism doesn’t accept the notion that life is suffering, or carries with it certain duties that must be fulfilled, or feelings that must be repressed. Rather, an objectivist ethic insists on exaltation, love of life, celebration in the bliss of being. It’s hungry and proud, fearless, shameless, sensual and visceral. But this does not imply blind hedonism, indulgence for indulgence’s sake has no purpose outside of the present moment. It does not lead to long term health or happiness. Eating a pizza every night of the week may taste good, but deep down it doesn’t feel good. For pleasure alone is not the cause of value, it is the consequence of achieving it.

Objectivism holds that man should have self esteem, but this must be earned. It is the consequence of having confidence in your reason and purpose. We are not born with innate knowledge or values, they must be discovered and adopted for ourselves. When you act in accordance with your self defined ideals, this makes you feel good, for you are striving towards something which your mind has deemed worthwhile and meaningful. You know why you act and what you will and wont do. You’re not guided by mere whims, but self-appointed principles. So long as you adhere to your own standards, so long as you never do anything that you are not proud of, then the judgements of other people cannot hurt you. If you are faithful to yourself, then self-esteem comes from within. It does not need to be earned by the approval of others.

Nowadays we tend to think of ego as a bad thing. “Egotistical” suggests someone who is self-righteous and self-obsessed with an inflated sense of self-worth. Even worse, it implies someone who is willing to sacrifice others as a means to their ends, who believes that their very existence makes them superior. Instead of being good because you have cultivated virtue, you’re good simply because you’re you. Your sense of self-esteem is unearned, it is an effect without any proper cause. This form of ego cannot survive on its own, it requires external validation from others in order to sustain the lie. It is status-seeking, superficial, shallow, and ultimately unsatisfying. Bad ego must continually work to evade reality in order to support its own self image. And by now I hope we know that reality cannot be avoided. Not forever. Not without consequence.

Good ego, on the other hand, you can consider as your sense of self. Your consciousness, your “I”, your epistemology, your sensory experience, your subjectivity. It is everything that connects you to reality, and without that, you are nothing at all. A good ego knows that the world can be mastered, but it must be obeyed. It cultivates confidence and self-esteem by trusting in its perceptual and conceptual capacities. It takes no authority to be higher than its own, while knowing that reality must be the final court of appeal. A good ego grows by being true to itself, through following its own reasons, passions, and purpose. It has nothing to do with how other people view you and everything to do with how you view yourself.

Are you capable or culpable? Are you actively working to evade reality, or do you know that it must be your only friend? If you wish to achieve any amount of success in life, you have to decide that you are capable. Very few success stories are born without a certain amount of pathological self-confidence. If you don’t believe you can do it, there’s no reason why anyone else should. Superstars are egotistical in that they pursue their goals unabashedly, they won’t let anyone else tell them what they can and cannot do, they follow their own mind and vision. But at the same time, they know that they must put in the work, for dreams without actions are simple delusions. If you are failing to achieve your goals, the only option available to you is to improve yourself, to work harder, to be better. So a certain amount of humility is required too—for you only deserve what you are willing to earn. Of course, these principles are by no means a promise of success, but they are the best possible path available. I’m not for a second pretending that life is fair, or that people get exactly what they deserve, but morality isn’t about what life throws at you, it’s about how you react to it. And so long as you stick to your own values and reasons, so long as you put in your best possible effort, then you’ll know any failure or hardship which befalls you is not your fault, for you did everything you could have done.

So, here’s my recommendation: pursue life like you can do anything and see what becomes possible. This is what Jordan Peterson means when he talks about adopting the greatest casual load you can bear. This pursuit is both the most challenging and also the most fulfilling. And like they say, shoot for the moon and even if you miss you’ll land among the stars. Believing you can do anything and trying is always better than doing nothing at all. And as I alluded to last episode, reality unfolds in accordance with your expectations. Opportunities will reveal themselves to you only when and where you decide to look for them. So pay attention! Look and listen, and soon you’ll start to find that there are little clues everywhere. Put your intention out into the world and it will find a way of coming back to you. I think that deep down this is the purpose of prayer. When you send a little wish out into the universe and you truly believe that it can be fulfilled, it’s more likely to come true, because you’ve opened yourself up to the possibility. The same principle applies to the concept of manifestation, or the law of attraction. These ideas work because they force you to adopt an optimistic attitude, and the broadest appetites produce the best results.

Another way of saying this is that you should approach life like the world is your oyster, or like a single player video game. You might load in without any items or knowledge, but there is an automatic assumption that achievement is possible, you just need to go out and explore a little. Even if you come from nothing, this doesn’t say anything about what you could be capable of. You may have noticed that it’s a common trope for the heroes in stories to start out as penniless orphans, with nothing and nobody to rely on but themselves. But what makes a hero? They are independent and courageous, confident and compassionate, ambitious and industrious, resourceful and resilient. They are driven by their own principles and for their own purpose, improving themselves and the rest of the world as a consequence.

So I know what you’re thinking. “Okay, I get what you’re saying. I know what I need to do. But what should I do? How do I figure out what my purpose is?” The answer is simple: start from the beginning. Where are you? Who are you? What are you working with? What are your strengths and weaknesses? You need to embrace these things as both cause and cure. We all come from a position which is entirely unique, and this is an asset. You have a certain set of specific knowledge and experience that is baked into your identity. No one can compete with you on being you, so what is something only you could do? That is what you should pursue. Follow your own interests, talents, and passions, otherwise you will be outperformed. Use your own unique position to your advantage and you will find a purpose that is meaningful, that feels inevitable even, like your own personal destiny.

I think determinism can either lead to despair or heroism. You are the product of unchosen factors, yes, and you will carry those influences with you throughout your life, they make you who you are. But what you are is more than what you are made of. You do not need to be defined by, or beholden to, anything which does not serve you. What you are, what your consciousness enables, is your ability to make choices. To adapt, to overcome. Understanding why we are the way we are allows us to reinvent ourselves when necessary. This is by no means easy, but it is possible to reprogram your mind. You don’t have to be anxious or depressed if you don’t want to be, but you will continue to be that way until you choose to become otherwise. You have to learn to forgive and integrate your past, for you cannot be blamed for it. It had to be that way, the only thing you can do now is choose to move forward from it.

So you do not have a free will that is unconstrained by causality, but you do have your will, a personal conception of and relationship to life that should not be sacrificed to any other standard. “When you really want something,” so says The Alchemist, “that desire comes from the soul of the universe.” And I really believe that to be true. The most meaningful drives in our lives aren’t accidents, they are a consequence of our very essence. And if you don’t know what you want out of life yet, that’s fine. For now, focus on developing yourself. Sort yourself out, clean your room, get your life in order and that way when desire or disaster comes calling, you’ll be ready for it. Afterwards it will be obvious that things couldn’t have happened any other way.

Part #7. The End And The Beginning

You return to the gates of UM and are surprised to spot Tru already standing outside.

“Yoo-hoo,” says Tru, “I’ve been waiting for you.”

“How’d you know I’d come back?” You ask.

“Oh, they always do,” he replies. “Now tell me, have you found your reason?”

“I think so,” you say.

“So, why should the town of UM let you in?”

“Mu,” says you, looking straight at Tru.

“Very good,” says the guard with a grin, standing aside to allow you in.

Continue to Part 6: The Structure of Freedom

Wonderland is a free publication that outlines a philosophy and political vision for the 22nd century. To support my work and receive updates on new posts, sign up for a free or paid subscription.

Share this post