Wonderland - Season I Complete

Table of Contents:

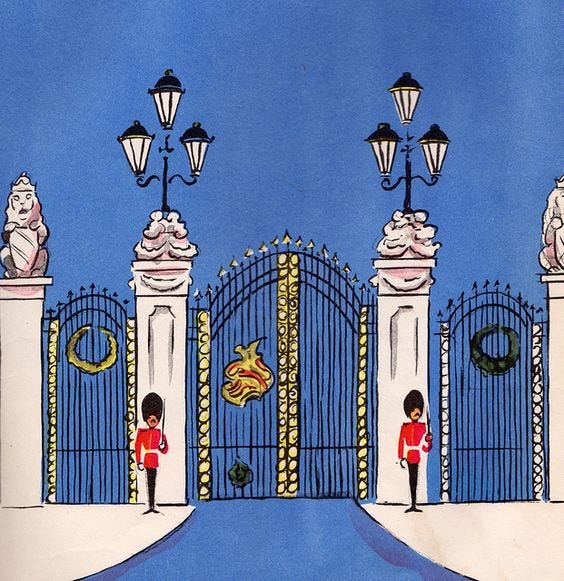

1. Philosophy: Who Needs It? - P1: The Maze - P2: Deny - P3: Might - P4: Rely - P5: Right 2. The Metaphysics of Complexity - P1: Mathematical Efficiency - P2: Adaptation in Motion - P3: Governing Features - P4: The Metaphysics of Complexity 3. Emergence & Epistemology - P1: Aunt Hillary - P2: Critical Realism - P3: Social Science 4. Free Will, Ethics, and Religion - P1: Ant Fugue, Phew! - P2: Science, Spirituality, Sam Harris - P3: The Croak and Call - P4: Just do it, Jesus Christ, Jordan Peterson 5. Hero: Moral Ego - P1: The Gate - P2: Good Reason - P3: The Woods - P4: Personal Purpose - P5: The Plan - P6: Self Esteem - P7: The End and The Beginning 6. The Structure of Freedom - P1: Welcome to UM - P2: Anarchy, Democracy, and Tyranny - P3: Here There Be Dragons - P4: Money, Value, and Virtue - P5: The Princess in the Palace - P6: Royals, Realms, and Patchwork Politics 7. On Land - P1: Power & Protection - P2: Dealing with Dragons - P3: Within the Walls - P4: What Else to Explore 8. Protection & Police - P1: What is Protection? - P2: The Guardians - P3: The Community 9. Rights & Responsibilities - P1: The Contract - P2: Children & Dependents - P3: Becoming a Citizen 10. Commerce & Contracts - P1: Contracts - P2: Rules & Regulations - P3: Intellectual Property

1. Philosophy: Who Needs It?

Welcome to Wonderland. This series will present a cohesive philosophical framework from the bottom-up. It begins with the value of philosophy itself and then starts to explore the realms of metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and morality. The second half then delves into politics and investigates the proper functions and role of government. But as the root of all ideas is philosophy, we are going to start with that. The question today being: What is philosophy? And who needs it? My answer is everyone, and I am going to try to convince you why. Let’s start off with a story...

Part One: The Maze

I want you to imagine that you are lying in a sunny field, and out of the corner of your eye you spot a flash of white. You sit up, and realize it’s a rabbit, in a waistcoat, with a pocket watch. Knowing where this story goes you chase after it, and soon find yourself tumbling down into wonderland. But, upon landing, you quickly realize it is not at all what you expected. There is no hallway full of doors, or table with instructional food. Instead, you find yourself in a completely novel place. You have wound up somewhere inside of a great hedge maze. The walls of which are too tall to climb or see over, and too dense to pass easily through. You explore a little, looking for the white rabbit, or at least, a way out, but find nothing. Just a seemingly endless array of hedges and pathways going off in every direction. You start to worry. What have I gotten myself into?

You wonder. And you look around, with three questions on your mind:

Where am I?

How can I discover it?

What should I do?

Alright. let’s pause and talk about what any of this has to do with philosophy. Now, the maze in this story is going to be a metaphor for life. And just like Alice lost in Wonderland, we have all found ourselves thrust into this big, beautiful, confusing world, and are doing our best to discover what rules govern it, what tools we can use to explore it, and what on earth we should do while we are here. The questions you must confront upon finding yourself lost in Wonderland are the same questions every person must consider living here, on earth.

Of course, some people would say that the answers are self-evident. Where am I? Well, I live in Canada. How do I know it? Oh, it’s obvious! Just look around. What should I do? Hmm, well that one is a little trickier, but, probably whatever everyone else is doing? Or, whatever I’m told? The only problem is that these answers are not very meaningful or fulfilling. They speak to the elements of our daily lives which are superficial, rather than fundamental. And they are completely unhelpful the moment you find yourself in a novel situation, like lost in a maze. This is because the conventional answers speak only to the contextual nature of the world you are living in—not the fundamental one.

Philosophy is the study of the fundamental nature of existence, of ourselves, and of our relationship to existence. You might notice that these three areas align with the three questions posed in Wonderland, and they represent the three primary domains of philosophy.

The study of the fundamental nature of existence is known as metaphysics, the answer to the question, “Where am I?” Metaphysics asks: are there firm and stable laws which regulate the universe? Or are things entirely relative and relational? Is there a consistent, coherent structure to reality? Or is everything random chaos? Does reality exist independent of our minds? Or as a product of it? The nature of your actions, attitudes, and ambitions will differ according to which set of answers you come to accept. But no matter what set of conclusions you reach, you will be confronted by a corollary question: “How do I know it?”

Epistemology is the study of our relationship to existence and how we acquire knowledge, the answer to the question, “How can I discover it?”. Epistemology asks: is it possible to acquire knowledge about the nature of reality? And if so, how? Are our senses reliable tools to navigate the world? Or are they easily influenced and impressionable? Do we learn through reason, or revelation? Are our emotions and intuitions valuable sources of information? Or are they irrational and fallible?

From these two branches, a third emerges: ethics, which is the study of ourselves and what constitutes moral action. The answer to the question “What should I do?” Ethics asks: is moral action possible, or, desirable? And if so, what does it look like?

So, if the maze is a metaphor for life, and philosophy is represented by the questions you must confront in order to escape the maze, then this story is going to demonstrate the consequences of different sets of belief. Either reality exists to be contended with, or it does not. Either we are capable of acquiring knowledge about the world, or we are not. Either we can act in a way which is purposeful and productive, or we can not. You would think that these basic yes or no questions should have obvious answers, but right now we live in a world where we can’t even get on the same page about the fundamentals. Philosophy does not represent some abstract realm of questions without consequences. You are operating by a philosophy, right now, whether you realize it or not. And the answers that you come to accept will have a direct impact not only on your course of your own life, but also the lives of people around you, and, quite possibly, the fate of the world. So, let’s return to the maze and examine some of those consequences.

Part Two: Deny

You are currently lost inside of a great hedge maze, looking for a way out. You wander around for ages, but the further you go the more vast and complex the maze seems to become. You walk for hours, not knowing if you are moving closer to, or further away from a potential escape. Or maybe you are simply caught in a loop, retracing old steps without even realizing it and making no progress whatsoever. Eventually, after a few frustrating hours, you decide to stop and have a rest, considering the strange series of events that brought you here: chasing the white rabbit down into the hole, and discovering a whole new world that seems to be ruled by neither rhyme nor reason.

Suddenly it all makes sense, you realize that you must be dreaming. Of course! There is no such thing as Wonderland, what were you thinking? I’ll just pinch myself and wake up, you decide. You spend a good five minutes trying to wake up but nothing works. You start to panic. Where am I?! You wonder once again. How did I get here? How do I get out? Can I get out? How do I know any of this is even real? None of it makes any sense! If I am not dreaming, then am I stuck in some sort of sadistic simulation? Or, maybe I have died and gone to hell, destined to an eternity of trying to escape an endless maze… like Sisyphus.

You feel trapped, helpless, hopeless, and confused. Overwhelmed by the vast and complex nature of the world you have found yourself in, you do the only thing you can do: you curl up into a ball on the ground and begin to bawl yourself. Eventually, night starts to fall, and you can feel your stomach growling with hunger. But you ignore it, you have no interest in moving or looking for food or water. You have decided to accept the inevitable and surrender yourself to the mercy of the maze. Days pass by, and, eventually, you pass out for good.

Let’s pause again. Now, this outcome might sound a bit stupid, but it represents something important: this is what happens when you refuse to accept reality on reality’s terms—when you deny a metaphysical understanding of the universe. Winding up in Wonderland without any clue what to do, the first thing you might do is question the nature of your reality. Thrust into a world that feels too overwhelming to understand, your first instinct may be to insist that it cannot be understood at all. You might want to tell yourself that you are dreaming, or living in a simulation, or any other story that exonerates you from having to discover where you are. Life is vast and complex, and it may seem easier to try to deny it, to surrender yourself to the causal forces of the universe rather than attempt to master them. But, clearly this method is not very effective. To deny existence is to become a victim to it. You are alive, you are in a maze; that means something real. You can try to avoid this truth, to make it into something different or more palatable, to avoid the responsibilities of having to think, or act. But ultimately, the consequences of reality will catch up with you. Better to try to contend with it a little, first. So, let’s try again.

Part Three: Might

You wake up back in the maze, surprised to discover that the thirst, hunger, and deterioration from the previous days has vanished. Your body seems to have returned to the state it was in when you first entered Wonderland. Renewed with new energy, and, being familiar with the plot of Groundhog Day, you decide that there must be some way to conquer the maze, since, apparently, you won’t die trying.

You choose a new strategy: instead of wandering aimlessly, you decide to pick one direct path and commit to it—no matter what gets in your way. You walk forward for a little while and pretty soon encounter a hedge. But, instead of trying to go around it, you start to force your way through it, and begin the painstaking process of ripping apart leaves and twigs and branches. Eventually you’ve created enough room that you can squeeze your body through and out, onto the other side (acquiring a few scratches along the way). However, it is not long until you encounter another hedge and have to repeat the same tedious process all over again. After a dozen more iterations of this your entire body is covered in scratches and your hands are red and raw. But you persevere—determined to make it out alive or die trying, emerging from each hedge more shredded and bloodied than the one before it as twigs catch on and tear at open wounds. But every time you grow weak and willing to surrender, you simply turn around and look at how much progress you have made, and that knowledge gives you the courage to continue.

Finally, after days without food or water, you begin to break through a hedge and reveal an open field on the other side. You joyously force your way through this last hedge and tumble out of the maze, collapsing on the other side exhausted but victorious. You decide to rest for a moment and close your eyes, enjoying your newfound freedom. Unintentionally, you drift off, and when you wake up you are overwhelmed by a sense of dread, as you realize that your wounds have healed, and you are once again back where you started, lost in the middle of the maze. But this time, the walls have turned to stone—you’re not going to get away with that again.

So, what are the philosophical implications of this second strategy? Well, you have realized the need to accept and contend with reality, rather than deny it, but you are refusing to play by the rules of the game. You have decided that the structure of the maze, the logic which dictates its form, is unimportant, since you have discovered a way to work around it. Therefore there is no need for you to acquire knowledge about the world, since you are able to manipulate its structure by sheer strength and force of will. But, as we all know, might is not right, since it is not a consistent principle. While forcing reality may reap you rewards in some circumstances, it is an unreliable tool. Your success was an accident of your environment; if the walls had been made of stone to begin with, you still be just as lost as you were in the first scenario. You have not adopted an epistemology that allows you to gain any knowledge about the rules which govern your environment. Therefore, the outcome you achieved, breaking through to that open field, was unearned. You cheated reality rather than mastered it, and this method will only get you so far. It is a bad guiding principle of behaviour since it cannot be transferred across different circumstances. People have different capacities for physical strength, and strength alone does not demonstrate moral authority; it is randomly distributed and inconsistently effective. Moreover, this brutal process of forcing reality to bend to your whims is agonizing to engage in. It does not feel right because it is not right, and it doesn’t last. We all know this. It’s like that old proverb of teaching a man to fish—if instead of learning how to fish yourself you go kill the fisherman and eat his food, but then later you go hungry since now there is no one around who knows how to fish! In other words; force is unsustainable. Failure to adopt real solutions to problems means that you will continue to encounter them. This is because you have not discovered anything meaningful about the system you are in. Breaking apart the form of the maze for your temporary success does not solve the puzzle, for you must abide by the rules of the game. Force alone is untethered to reliable knowledge or consistent principles, and is therefore not a viable solution. So, let’s go back to the maze.

Part Four: Rely

The hedges have turned to stone, and you are lost once again. You are ready to cry out at the futility of it all when you notice something else is new. Lying on the ground in front of you is a scrap of paper. You pick it up, and are shocked to discover a list of directions. A series of “left’s”, “right’s”, and “straight ahead’s” running down the length of the page. It seems like someone is trying to help you out! Elated, you immediately start racing through its prescribed path, running through the stone hallways with confidence and zeal.

However, it is not long until you encounter a problem—you reach a junction where the paper says you must go straight, but only left or right are viable options. Did you possibly miss a step? Or take a wrong turn? You try to retrace your steps, but quickly become frustrated as you realize that you have no clue when, where, or how you lost your way. Then you realize that maybe you didn’t even set off in the right direction. Since left and right are all a matter of perspective, if you had been facing the opposite way when you began you would have taken an entirely different path. You crumple the paper up in defeat, realizing that you are too far from your starting point for it to have any utility. Even if the instructions had been useful once, there is no way that you can apply them now that you are lost again.

You chuck the note aside, but as you do another one flutters down, like a gift from God. This one, instead of relative directions, contains an objective drawing: an image of a maze. Finally, a guide with real utility! Since it doesn’t matter where you start, you can always orient yourself relative to the map to figure out where you ought to go next. You study the diagram and start trying to compare it to your surroundings, looking for key junctions or defining features which could help you get your bearings. You spend a few hours walking around looking for similarities between your maze and the paper one, trying to figure out where you are in relation to the map. But every time you think you have it figured out, you take a turn and encounter some obstacle or pathway that is not accounted for in the paper analogue. Eventually, you are begrudgingly forced to admit that although you have a map of a maze, it is not a map of your maze. Any similarities are completely coincidental, and knowledge of one will not help you navigate the other.

Time to pause and analyze. If the last scenario represented a rejection of knowledge in favour of might, then this one represents the problem of trying to acquire knowledge through appeals to authority. In other words, how information can be unreliable when gained through someone else’s experience, rather than your own. It doesn’t really matter where these notes came from or how they got to you—they could have been left behind by other adventurers, or the product of divine intervention. The point is that they represent cultural norms, accepted values, and inherited knowledge. While these guides may have been viable in one time, or in one circumstance, that does not necessarily mean that they carry over to your own. This is because in order to use these tools you have to start from a certain position (like the list of directions), or in a certain context (like the map). And while the maze is a metaphor for life, there is no reason to assume that any two mazes are alike. That is to say, the things that you need to do to achieve success in your own life might be very different than the process that worked for somebody else. Maybe some role model of yours says that the key to their success is going for a run every morning and drinking a green smoothie, but repeating these habits in your own life does not guarantee that you are going to have the same outcome. Similarly, many religious beliefs and practices come from a time very different than our own, and while they may have had practical utility back then, it is important to be consistently questioning and evaluating to what extent those moral standards and norms still hold true. Systems of understanding that worked for a certain time, context, or circumstance, may very well now be outdated relics of the past. This is why blind obedience to authority is never an effective way to conduct yourself through life. You must be able to independently assess how useful or relevant a given idea is by comparing it to your objective reality. Instructions alone are not enough, we are looking for principles of solution, not prescribed paths. Let’s try again.

Part Five: Right

Upon discovering that the map will not help you any more than the note that came before it, you are once again overwhelmed by a sense of dread and frustration. “If only there was a way to find the right path!” You cry out. “All I need is one right path that would show me the way!” As you say this, an idea dawns upon you. An idea so elegant, and so simple, you are shocked you had not considered it before. What if, instead of adhering to a certain direction or form, as the notes had suggested, you adhere to a certain methodology. That is to say, a certain means of solution rather than a specific mode. To accept reality, and not attempt to deny it or wish it away. To accept the logic, the structure, the rigidity of the maze, rather than trying to cheat it through force. And to accept the uniqueness of your own circumstance, rather than trying to replicate the tactics that might have worked for others. To look for the consistent principles which will not vary depending upon the context you find yourself in.

Where am I? I am lost in a maze. How can I discover it? Through my own senses and mind. What should I do? Use the tools available to me to commit myself to the only thing I know for sure: the rule of rules. The walls of the maze. Its limitations are its structure. The only clue you need to escape the maze is the maze itself. It creates its own rules. To discover them, you need only to commit yourself to the system you have found yourself in, and follow through.

You put your right hand on the right wall of the maze and walk forward, allowing the structure itself guide you to where you need to go. It will be a long process, a tedious one, you will have to encounter every dead end in order to determine which direction will bring about a promising lead. But in doing so, you will eventually discover the way out. Strict adherence to this one consistent thread will guide you to where you need to go next. You are using the system itself to discover how you should navigate it. This is a first principle. One that works for all mazes, across all circumstances.

This is what philosophy provides. A framework that teaches you not what to think, not where to go, but how to think: the process through which you can tether yourself to reality and in doing so navigate its structure for yourself. Through the commitment to metaphysical reality and epistemological capacity, a moral duty naturally arises. Follow that thread, that tether, that wall, wherever it may lead, and in doing so you will discover the nature of the world around you and how you ought act in it.

My philosophy is committed to this principle of process: the notion of truth and our capacity for discovery. Once accepted, this premise cannot fail you. It is not based in your whims or your wants or what someone else told you, but the world exactly as it is. It is only once you have discovered this guiding principle, this thread of reasoning that pulls you forward, that you are finally able to escape the maze, and explore the rest of Wonderland.

This is what comes next. Now that I have described what philosophy is, and why you need it, I will outline what exactly my philosophy looks like. I have demonstrated why I believe metaphysics and epistemology are necessary, but I have not yet described what my personal interpretation of those domains are, only that they exist and can be known. So, in part two I will talk about metaphysics. I have a commitment to reality, but what is the process through which reality unfolds? What are the rules of the game? How does the maze acquire its structure? What are the fix and flux points which combine to give us the forms we are familiar with? My answer is complexity.

2. The Metaphysics of Complexity

Complexity theory, or the study of Complex Adaptive Systems, represents something fundamental about the nature of the universe. Once you understand how complex systems work, suddenly many areas of life will make more sense and be easier analyze. To better comprehend how these systems function, we are going to go back down the rabbit hole into Wonderland to explore by analogy. Our last chapter ended with you escaping the maze, equipped with philosophy as the tool which will help you navigate the world. This means using your own senses and mind to perceive and integrate your surroundings. But what is the fundamental nature of the universe we are trying to understand? What are the underlying mechanisms which determine what can exist? How do they work? Well, let’s explore a little...

Part One: Mathematical Efficiency

You walk out of the maze and are greeted by a vast forest. Not knowing where to go, you decide to go straight ahead until you encounter something of interest. But there isn’t really anything interesting at all, just trees. So, after a while you decide to study one of those. You plop down on the ground with your back up against a truck, looking up at the canopy of branches above you. As you examine the web of interlocking lines, you start to notice the rules which give the trees their form. How the same patterns repeat over and over again. Each branch grows, sometimes with a few offshoots, until eventually splitting up into two smaller branches. The process repeats all the way up to the top of the tree, going from one to two to four to eight and so on. Each time a split occurs, the overall proportions remain the same. You can imagine how cutting off a branch at the top of the tree would create a much smaller version of the whole, maintaining the same trunk to branch ratio. Except, of course, for the leaves.

But the leaves too, you notice, picking a fallen one up off the ground, follow the same pattern of self-similarity. The stem turns into a vein that runs down the centre of the leaf, and from that main vein smaller ones shoot off on either side, and then even smaller ones grow off of those. But then the pattern seems to be lost, as the capillaries lose their more formal arrangement and turn into seemingly random networks. But are they? As you hold the leaf up to your eyes, you notice that the dry mud cracked on the ground beneath you shares the same pattern. With the cracks, like the capillaries, always meeting at 3 or 4 point junctions, breaking up into ever smaller subsystems. Now why would this be?

As you consider this, you hear a low rumble as the skies of Wonderland quickly turn overcast and a thunderstorm begins to roll in. You watch as the first bolt of lightning shoots down. However, instead of a quick flash, the skies of Wonderland allow you to see the entire process in super-slow motion. You watch as the lightning branches down from the sky in a pattern that looks almost identical to the trees growing in the forest; with a network of leaders splitting up and trailing down in different directions. The leader that makes contact with the earth first then sends a second, much stronger bolt back up into the sky. What is going on here?

The electricity is stretching out, seeking the path of least resistance. Once connection to the ground occurs—lightning strikes. The same process is happening to determine how drying mud cracks in a way that relieves the most tension, and the capillaries on the leaves form to allow for the most efficient transportation of nutrients. So too are the trees, governed by this process which is driven by ease. Other examples include the hexagonal hives of honey bees, or soap bubbles drifting in the breeze. What you are witnessing are the manifestations of mathematics in nature. For the same reason that plants grow in Fibonacci spirals, all of the natural world operates in a way that seeks to minimize energy expenditure. Getting the most bang for your buck, if you like. This implies that many seemingly distinct phenomena are actually regulated by the same underlying drives and mechanisms. Which is why the trees, the leaves, the dried mud, and the lightning all share some similar features. The patterns that you see repeating everywhere are not accidental, but innate. This is due to a few very simple decision making rules which lead to intelligent, complex behaviour. That’s all math is really: simple rules with complex consequences. Although not comprehensive complex adaptive systems in and of themselves, manifestations of mathematics in nature provide some key insights into how complex systems work.

Part Two: Adaptation in Motion

Complex adaptive systems are composed of individual agents which interact with one another as well as their environment, giving rise to emergent behaviour which cannot be reduced to the sum its parts. They can be found almost anywhere, from the activity of ant colonies to the formation of sand dunes, flocks of birds and schools of fish. Their dynamics influence the evolution of plants and animals, interactions within ecosystems, and even the weather. And that’s only in the natural realm! Complexity is even more abundant in the social sphere. Some examples include financial markets, traffic jams, the rise and fall of culture, the evolution of language, the internet, social movements, academic citations, machine learning algorithms… It would probably be easier to list the realms of human activity that aren't governed by complex systems, rather than the ones that are. But what’s really interesting about complex systems isn’t where they are, because you can find them almost everywhere, but how they work.

I’ll explain through the classic example of an ant colony. Any complex system contains three main components: agents, drives, and signals. In an ant colony, the ants are the agents, the food they forage is the drive, and the pheromone trails they leave behind are the signals. A single forager ant will wander along until it discovers a source of food, which it then collects and brings back to the colony. But it leaves behind a pheromone trail which is then used by other ants to guide them to the food supply. As more ants harvest from the same source the signal will become stronger and recruit even more ants, until all the food is harvested. After this point, new ants that follow the trail only to discover no food will return home without leaving a signal, therefore dampening that signal over time and allowing new food sources to be discovered. Now, if all of the ants in the colony directed all of their attention to only harvesting this one resource, better, more fruitful alternatives may be overlooked. Thankfully, ants are not very intelligent, and some will wander off the beaten path, allowing for the possibility of better alternatives to be discovered. In this way, complex systems use random error to their advantage. As Nassim Taleb would say, they are antifragile. The imperfection of their agents makes them stronger, rather than weaker.

Another example of a complex system would be how memes spread. In this case, internet users are the agents, their drive is entertaining or interesting content, and the signal is how much engagement a piece of content receives. A funny meme posted to a message board like 4chan will be picked up by community members and shared to other online spaces, where the same process reoccurs on larger and larger scales until it eventually hits the front page of Reddit and is being talked about by late night hosts. Of course, a given meme doesn’t stay relevant for long, so the same cycle must keep recurring to keep up with current culture. This is why they are called complex adaptive systems. They are not static, but constantly changing and evolving in relation to a given context or environment.

I should mention that complex systems are not that same thing as complicated ones. Complicated systems have linear, 1-1 cause and effect relationships, like the inner workings of your car. There may be lots of different parts and components working together to produce a given outcome, but the parts are not interrelated. You slamming on the breaks of your car will have no impact on the motion of your steering wheel. Whereas in a complex system, it would. Complex systems are nonlinear, meaning that the agents of the system are interrelated in a way that makes causality much more difficult to follow. A small change at one point in the network can create a ripple effect which produces much larger consequences in seemingly unrelated areas.

This idea of nonlinearity has another important consequence—complex systems are entangled. Their components cannot be broken apart and studied in isolation using the methods of traditional science, for information is lost in the process. It is not just the agents that must be studied, but also the relationships between the agents. Imagine trying to understand how an ant colony operates by taking each ant and observing it in isolation—I doubt you would get very far. The interactions between the agents have meaningful consequences. While made up of individual components, the system is not simply the sum of its parts. It has certain unique, emergent characteristics.

So, how can we study complex systems if the whole is too specific, and the parts are too general? Well, they are all mediated by and subject to certain governing features. Despite taking on such different forms as social networks and sand dunes, there are consistent dynamics that all complex systems share. If we can understand one system and the mechanisms which govern its behaviour, it becomes much easier to take those insights and apply them elsewhere.

Part Three: Governing Features

Different complexity theorists all have slightly different opinions about what traits define a complex system, for their governing features often overlap and interrelate. I have selected a few key concepts to outline and define, and hopefully by understanding

these ideas you can begin to develop an intuition as to what complex adaptive systems are and how they work.

To start, complex systems are self-similar: I alluded to this concept at the beginning of the chapter back in Wonderland—the fractal-like way where the same patterns and features can be observed at different levels of analysis, zooming in or out. Trees and lightning bolts are composed of miniature versions of themselves which share the same traits. Similarly, financial markets or weather patterns can be analyzed and understood on a global scale, or by country, or by city. Each contains its own internal dynamics while simultaneously being subject to influences from the broader system it is nested inside of. You can also apply this idea to the internet, where communities are subdivided into smaller and smaller niches. For instance, you can get online and go on social media. Specifically, Tumblr. Specifically, fandom Tumblr. Specifically, the Doctor Who fandom. Specifically, Doctor Who fanfiction. Specifically, Doctor Who fanfiction set in a setting where… you get the idea. In each of these progressively smaller communities you will find that there are certain key players who are well known and carry a disproportionate amount of influence.

In fact, influence on any level of analysis follows a power law, or Pareto distribution, where 20% of the agents will account for 80% of the overall influence. It’s important to note that when I say agents here, I do not necessarily mean people. If you are looking to analyze the Amazon rainforest, then trees might be the agents, where 80% of the density is concentrated in 20% of the plants. We tend to think of normal, or bell curve distributions as being the universal default, but this is untrue. Random distributions only occur when the agents are independent from one another. So people’s heights or shoe sizes could be charted on a bell curve, but not their incomes. When agents are interdependent, like in a complex system, random distributions no longer apply. In fact, complex systems are so ubiquitous that if you are ever unsure of a statistic, you can simply make it up with a relatively high degree of accuracy. For instance, 20% of books published make up 80% of sales, 20% of cities hold 80% of the global population, 20% of roads get driven on 80% of the time… you get the idea. But why is this the case?

I like to call it the “law of gravity”, or, that which has, gains! The rich get richer. If two actors of equal talent go in for an audition and one lands the part, then they are more likely to get more acting jobs in the future. Having garnered one major role increases the odds that you land another. A book that ends up on the New York Times bestseller list is bound to sell more copies than one that doesn’t. A stronger signal, be it book sales or pheromone trails, means that more agents are likely to go down that path in the future. This is what we call a feedback loop. Understanding how these dynamics work can help us become aware of their potential shortcomings. It is completely possible for a feedback loop to start perpetuating inefficient or outdated systems. For example, the QWERTY keyboard. QWERTY is an intentionally inefficient typing system, designed back in the day of mechanical typewriters where typing too quickly could jam the keys. Now this is no longer an issue, but since everyone learned to type on QWERTY keyboards their legacy has remained, and we are all much slower typists than we could be as a result of this. Efforts to introduce better, alternative keyboards exist, but established norms can be hard to escape when we’ve all grown accustomed to a certain way of doing things. Being mindful of how feedback loops work can help us to disrupt them when necessary. But we have to know why we are disrupting them, what’s changed?

This goes back to the idea that complex systems are adaptive, meaning the behaviours of a system will adjust and change over time. This can either be in response to a shift in the system’s internal state of affairs, or the external environment. The most popular example of this is Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection. A common misconception about Darwinism is that Darwin believed in “survival of the fittest”, while really what he championed is, “survival of the best suited to the environment”. This more nuanced position takes into account the fact that the environment is constantly changing and evolving. Therefore “fitness” cannot be conceptualized in a vacuum; it must exist in relation to a broader context. This process works through variation, selection, and retention. For biologists, this refers to genetic mutation, but it can also apply to ant trails, book sales, or scammy emails.

A bot that has been programmed to send emails soliciting money will probably vary the types of messages it sends, and then generate more messages depending on which style is the most successful. As people learn not to trust mysterious messages from Nigerian princes, the program will then have to adjust its behaviour and employ new tactics. That being said, there are certain attractor states in all complex systems that adaptations will gravitate towards. In the realm of evolutionary biology, camouflage is a strong example of this. Certain patterns and colorings will consistently crop up in insects, amphibians, and other animals. Despite coming from dramatically different evolutionary trajectories, some adaptations contain universal utility. Although again, advantages always exist in relation to a given environment. In some circumstances, a multiplicity of equally viable attractors is possible, while other contexts demand a singular solution. An example of this may be the path you take to cut through a forest. Depending upon the obstacles at hand, there might be one ideal path which is clearly the most efficient, or there might be a few different options that are all equally viable.

As was said earlier, complex systems are nonlinear, meaning that the size of an effect can be much greater than the initial cause. Consider how a rock jostled from the right nook on a steep cliff will cause an avalanche, or the straw that broke the camel’s back. There are certain tipping points in complex systems where a small, seemingly irrelevant push will create very large consequences. You might have heard of this phenomenon referred to as the butterfly effect, where it is said that the flapping of a butterfly’s wings can cause hurricanes; or how some small difference in initial conditions can produce dramatically different outcomes. This is because, due to the feedback loops mentioned earlier, a minor cause can compound into much greater consequences. Maybe a single wandering north discovers a food supply which ensures that the colony having enough food to survive the winter. Or maybe one upvote on a meme makes the difference between it going viral or never being seen again. We like to think that the influence of our actions is limited to ourselves, but complexity theory suggests that the stakes may be far greater than you could possibly imagine.

Complex systems form from the bottom-up, meaning they are driven by the simple decisions of individual agents. If you have ever wondered how flocks of birds or schools of fish move in such beautiful patterns, here is your answer. There is no head bird or fish that is calling the shots, each one is simply reacting to the movement of its neighbors while maintaining a certain speed and distance. These simple decision making rules are what compound and lead to complex outcomes. A great example of this is how researchers have started using slime mold to map roadways. This unique type of mold will, like ant colonies, spread out and create networks in relation to available food sources. A team of researchers took oat flakes and arranged them in a pattern that mimicked cities surrounding Tokyo. Within a few hours, the slime mold had spread throughout the flakes and taken on a shape that looked nearly identical to Tokyo's subway system. This subway system had been meticulously designed by a team of expert engineers, and yet some unintelligent slime mold was able to replicate their results with an amazing degree of accuracy. Without any centralized control or planning, an organized, efficient outcome was achieved. But how is this possible?

This leads us to the final and arguably most interesting component of complexity, which is that complex adaptive systems have emergent characteristics which cannot be reduced to the sum of their parts. Often, this emergence can look like some form of intelligence or hierarchical control. But you will not find these qualities within the individual agents—they only come to exist through the relationships and interactions between them. However, once these features emerge, they come to possess their own unique causal power. We understand this pretty intuitively in terms of culture; there is no government body or top-down control determining what music, food, or fashion is going to be popular. Our preferences are determined by the people around us. Once a certain fashion trend or fad food takes hold, it then starts to influence the behaviour of individuals. Causality begins to work in two directions. People make culture, but culture also makes people. This phenomena of emergence has lots if interesting implications when it comes to understanding consciousness, but more on that later. Now that I’ve outlined some governing features of complex systems, hopefully you are beginning to develop an intuition for what they are and how they work.

Part Four: The Metaphysics of Complexity

So, to tie all of this back to metaphysics. I do not wish to argue that all aspects of reality are innately complex adaptive systems, but they do consistently give rise to increasingly complex behaviour. They are anti-entropic, meaning they produce order out of chaos. They become more organized and more structured as time goes on, rather than less. And they can be found almost everywhere, both in the natural and the social realm. Understanding how these systems work increases our capacity to think critically about the environments we find ourselves in—the mechanisms that brought about their creation as well as possible shifts that could lead to their collapse. There are consistent rules at play, but they result in contingent and ever-changing outcomes. For this reason, an emphasis on complex thinking illustrates how any truth claim always exists in relation to a given context. But these truths emerge out of, and are regulated by, certain higher order mechanisms which are governed by consistent principles. This is the case I want to argue, especially because I think it has extremely interesting implications when it comes to what I call nesting objectivism and relativism.

If you recall, in the last chapter I described metaphysics as asking, “are there firm and stable laws which regulate the universe? Or are things entirely relative and relational? Is there a consistent, coherent structure to reality? Or is everything random chaos?” These questions essentially boil down to the timeless debate between objectivism and relativism. Now, the beautiful answer that an understanding of complexity provides is: both. There is fix, and there is flux. If you like, you can reframe these two seemingly contradictory stances in terms of the Taoist concept of Yin and Yang, chaos and order. Knowing “the Way” requires being able to traverse the fine line down the middle, straddling both extremes. There is no rigid, consistent, perfect Platonic form, but there are certain rules which govern how and why any given form manifests (although these motives may not necessarily be identifiable through so many entangled threads). Thinking complexly demands much more nuance than most interpretations of reality, precisely because things can never be boiled down to simply either/or. There are both objective truths and relative contexts at play.

My ultimate metaphysical argument is that we must focus on the broader processes which determine how reality manifests, rather than any particular manifestation. Specific structures matter too, of course, since they represent the very real constrains that you must learn to navigate, but they are much more context and path dependent than the meta-structures which determine their form. To go back to the metaphor of the maze, the particular form of your maze isn't as relevant as the rules which govern all mazes. The solution should allow you to navigate any given maze successfully. Understanding the underlying generative rules is always going to be more valuable than mastering a specific materialization. I think we have a natural intuition for this idea—concept formation is all about abstracting away from specifics towards more general principles. What makes a video go viral? Why does a tree take on a certain form? We are not interested in the reasons underlying any specific instance, but the mechanisms which are consistently at work upon repeated iterations.

Employing complex thinking is an extremely useful analytical tool, especially in social studies where natural scientific methodologies are no longer viable. For instance, try evaluating a truth claim like, “pink is a girl’s color”. Well, we all know this be true and untrue simultaneously. Obviously no color has innate, objectively gendered traits; 150 years ago light blue was the popular color associated with girls. However, we can trace an objective (although complex) path through history, fashion, and advertising to determine how, “pink is for girls” came to be a “true” statement.

Another example would be how everyone learns in history class how the assassination of Franz Ferdinand kicked off the start of World War I. You could conceptualize this event as a “tipping point” that set off a domino chain of reactions producing an effect much greater than the initial cause. The consequences of the Treaty of Versailles put Germany in a much weaker economic position, causing a growing support for the Nationalist Socialist Party years later. But linking Franz Ferdinand’s assassination directly to the Holocaust is much trickier. There were many underlying causes for the Nazi’s rise to power, and history is rife with competing interpretations as to which events held more causal power in determining a given outcome. Maybe the Holocaust was an “attractor state” which would have happened irrespective of the assassination, it’s impossible to know—there are too many entangled threads.

Martha will forever be my favorite Doctor Who companion because she understood this notion of causal complexity on her first time travel adventure, expressing concern that stepping on a leaf may lead to a compounding series of unintended consequences. Later in the show, the Doctor reveals that this is not an issue since there are fix and flux points in time. I think this statement gets at the heart of the idea I am trying to express here. In any system there are going to be certain attractor states which are inevitable products of the systems themselves, and other areas full of wiggle room. The notion that pink is for girls most likely falls into the latter category; it is probably a path dependent outcome which wouldn’t continue to arise upon repeated iterations. Understanding how these processes unfold allows us to try to evaluate which is which in a given situation. Another gendered truth claim is that, on average, women are more interested in people, whereas men are more interested in things. This idea can help explain why men and women tend to have different career interests. In societies that have done the most to promote gender equality, these differences are heightened rather than diminished. This would suggest that these differences are not the result of path dependent feedback loops, but instead the product of hundreds of thousands of years of evolutionary psychology—an attractor state signifying a much deeper truth.

In the broadest of strokes, I wish to posit that the notion that “truth” always exists in relation to a given environment, which itself is constantly shifting and evolving. But there are consistent rules which dictate a contingent structure; reality evolves through complex dynamics. Relativists, or postmodernists, emphasize how truth claims are contextual, and ever-changing. While objectivists, or realists, are interested in the consistent rules which cause a given truth claim to emerge. They are both attending to only one half of a much bigger picture. We must be able to synthesize and acknowledge how both of these forces work in tandem simultaneously. Neither can exist in isolation, for they are two parts of a greater whole.

So where do we go from here? If my metaphysics is grounded in complexity, then what implications does that have for epistemology? How can and should we go about acquiring knowledge? Well, as was said earlier, a special feature of complex systems is that they posses emergent characteristics. This concept of emergence has dramatic implications on what we are capable of knowing. The philosophy of science is then of utmost importance, and critical realism is a philosophical approach that I believe deals with these issues most persuasively. So, in the next installment I will begin to unpack critical realism and discuss what implications it has on scientific inquiry.

3. Emergence & Epistemology

Critical realism is a philosophical system which is concerned with the philosophy of science, or epistemology. Essentially, what we can know and how we can know it. Are our senses reliable tools to navigate the world? Or do they represent only one small part of a much larger picture? Can reality be studied through materialist, scientific methods? Or does such a reductionist view of the world obfuscate the truth rather than reveal it? These are the sorts of questions this chapter shall explore. But first, let’s pick up from where we left off in Wonderland. It was a thunderstorm, remember?

Part One: Aunt Hillary

From your spot under the tree you watch as the storm slowly comes to an end and the skies begin to clear again. The sun comes out, and you watch the forest come alive. You spot an ant trail on the ground next to you, trailing off into the woods, and you decide to follow it; hoping it might lead you to something interesting. You follow the trail as it connects back to a series of progressively larger and larger ones, until you are essentially following an ant highway, with hundreds of thousands of ants all marching in the same direction. They must be going back to the colony, you think. But instead of a hill, the parade of ants leads you to a little cottage tucked away in small clearing in the woods, with ant trails coming from all sorts of different directions and congregating at this central location. Tentatively, you tip-toe over their criss-crossing paths and approach the door of the cottage. But before you can raise your hand to knock, the door swings open, and you are greeted by a cheerful old woman.

“Oh, hello dearie!” She says. “Come inside, I’ve been expecting you!”

“I’m sorry, but who are you?” You ask.

“Oh, just call me Aunt Hillary,” she replies with a grin, ushering you inside towards a seat by the fire and handing you a hot cup of tea. “I’m glad to see you got my message,”

she says as you settle in.

“Your message?” You ask. She shoots you a wink but says nothing.

“What are all of those ants doing outside of your house?” You inquire.

“Oh, I’m sorry! I thought you understood,” she replies. “I’m Aunt Hillary, and this is the ant hill.”

“Oh! So they’re your ants?”

“Well, only to the extent that the cells in your body are “your” cells. I didn’t choose to have them, nor do I have much control over them, but they make me who I am, yes.”

“I’m confused,” you say. “You’re not an ant.”

“No, I’m not,” she replies. “No more than you are a collection of chemicals and cells, but that is what you’re made of, isn’t it?”

“I guess I hadn’t thought about it that way,” you say, taking a sip of your tea. “But how can you be made of ants if the ants are all outside while you’re sitting in here?”

“Oh child,” Aunt Hillary chides. “You forget that you are in Wonderland and here, looks can be deceiving. Here, look,” she says, gesturing to an open book. “Tell me what you see.”

“Looks like a dialogue of some sort,” you say as you examine the page. “Seems like the title of this chapter is ‘Ant Fugue’.”

“Quite right,” says Aunt Hillary. “A story written by a good friend of mine in fact, concerning this very topic. I can try to imitate some main themes of his for you now, if you like. You wish to know how I can exist independent from the ants which give me my form? Then first try considering where in this book the story resides.”

“Well, the words obviously.”

“Is that so? Not the letters?”

“Well, no, because the letters on their own don’t have any meaning. They have to be put into words in order to make sense.”

“And then the words are arranged into..?”

“...Sentences. Alright, I guess I see what you mean. It’s not just the words that matter, but the order in which they’re placed.”

“Precisely. Just as the same letters can be rearranged to create different words, the same words can be rearranged to create different sentences. It’s not just the parts that matter, but the relationships between them. The words on their own don’t have any more meaning than the letters do—they are symbols. And those symbols must be arranged into sentences in order to convey an idea, ideas which are then compiled into paragraphs and chapters to tell a story. But what happens if I were to remove an adjective from a sentence in the text. Would it be the same story, or a different one?”

“Well, I can’t imagine what difference a single adjective would make. So I’m inclined to say it’s the same.”

“So then the ideas, to some extent, exist outside of the words which create them, do they not? If, for instance, a hundred people were asked to tell the story of Hansel and Gretel, I’m sure each version would be a little bit different, but the main plot point and characters would stay the same. Just like how a translated version of this book would carry the same contents while being composed of entirely different characters. The medium is not the message.”

“Oh, I get it,” you reply. “The story somehow exists in a realm which is outside of and separate from the things which make up its telling. It’s not material, but conceptual.”

“Exactly!” Says Aunt Hillary with an approving smile. “And you and I are no different. The letters on that page are like the neurons in your brain, or the ants in my colony. Taken in isolation they possess no intelligence or agency, they are simply firing or foraging; playing their small part in a much larger picture. But just how letters come together to form words, neurons fire in clusters which activate symbols in your mind, and my ants operate in castes to perform different duties for the colony. However, they are as unaware of me as I am of them. They may make us what we are, but what we are is more than what we are made of. Your subjective experience of being is not the firing of neurons, but the manipulation of symbols. At some point along the way, you, as an emergent entity, came to possess an agency which can act upon the very things which make it up. Aunt Hillary is just an idea, and yet in some ways I am more real than the ants themselves. I control their behaviour, but I don’t exist in a material sense any more than you do. You are not simply a series of electrochemical signals, otherwise what role would your consciousness play? You are an active agent. And that agency is not simply a product of your neurons or your nature or your nurture. It is something new, something more. So the reason why I can sit here and drink tea with you while my ants roam around outside is the same reason why you can sit here and drink tea with me, while all of your neurons are stuck inside of your brain. You are not in your head, yet that is where you came from. So, where are you? What are you?”

Throughout Aunt Hillary's explanation you feel yourself overwhelmed by a wave of dizziness and dread. “I… I don’t feel so good,” you say, getting up abruptly from your spot by the fire and placing the teacup down on the table. In a distant daze you turn to walk out of the cabin and back, out, into the woods.

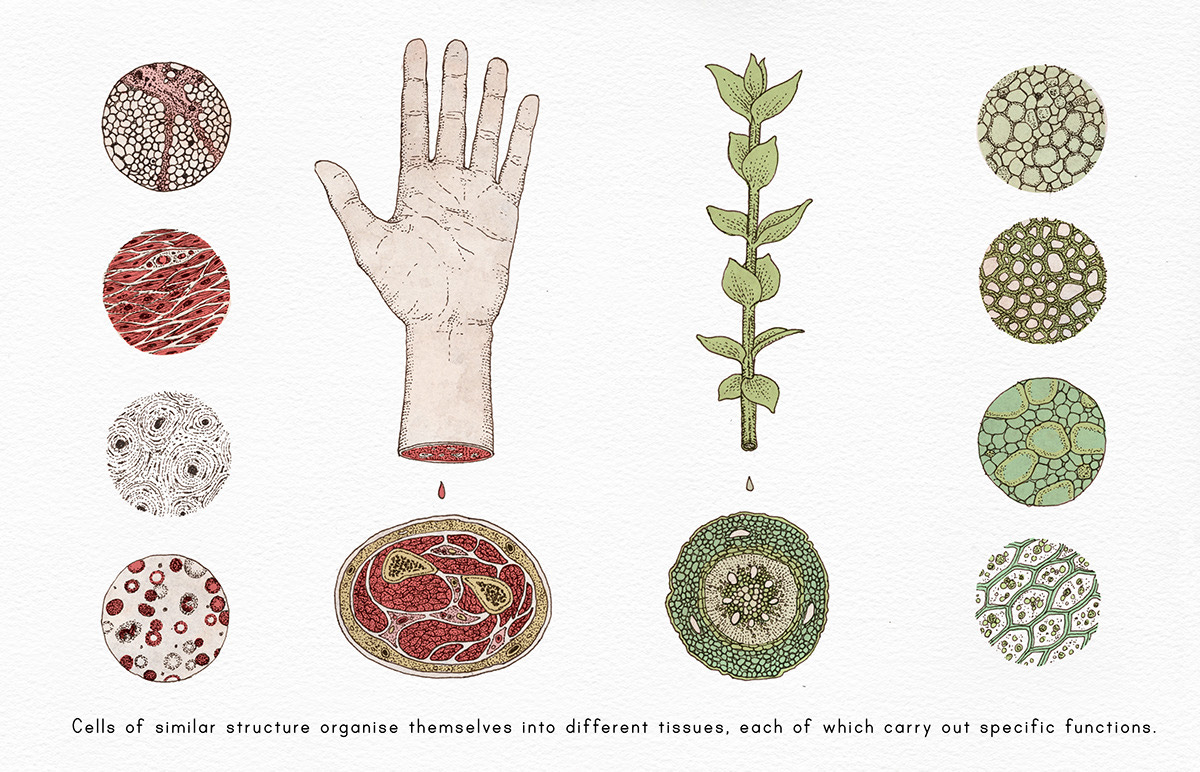

Part Two: Critical Realism

The central idea I am trying to convey through this ant fugue, inspired by Douglas Hofstadter's dialogue of the same name, is that reality exists in stratified layers. Each one emerging out of, yet not being reducible to, the one that came before. If you like, you can think of this in terms of different areas of inquiry. Mathematics leads to physics, physics to chemistry, chemistry to biology, and biology to psychology. At the most basic level, the firing of neurons in our brain is simply a collection of chemical computations, but that certainly isn’t what the subjective experience of consciousness feels like. We can use mathematics to describe neurology, but psychology is clearly a lot more complex than a series of equations. You cannot use mathematical models to predict psychological behaviour. Roy Bhaskar, the father of critical realism, described this phenomenon with the words, “it is true that the path of my pen does not violate any laws of physics, but it is not determined by any either.” So, how can we construct a view of reality that accounts for this uncertainty?

Critical realism is a philosophical system that was designed by Roy Bhaskar to deal with the implications of emergence, in terms of both what is and also what we can know. In philosophy, these are the domains of ontology and epistemology. Bhaskar’s critique

of modern science is that it prioritizes epistemology over ontology: emphasizing the ways in which we acquire knowledge while overlooking the fact that there may be some limitations to what is knowable through empirical methods. If reality contains emergent layers, then there is no reason to assume that all of it must be confined to the material realm. As Aunt Hillary demonstrates, the relationships between things can be just as, or even more important, than the things themselves. There may be aspects of reality which exist in a causal sense, but not a material one.

In other words, critical realists believe in an objective reality, but they acknowledge the fact that our ability to acquire knowledge is constrained. What we can know is limited, relative, and often context-dependent. Although the knowledge we gain about the world does speak to real truths, they are approximations rather than absolutes. It’s like that parable about the blind men and the elephant, wherein a group of blind men encounter an elephant and—being unfamiliar with its form—each touch a different part of the animal, leading them to come to different conclusions about the whole. The blind man who touches a tusk is going to have a very different interpretation than the man who touches the trunk. Each one of their subjective experiences is correct, just not comprehensive. The information they perceive must be situated inside of a broader explanatory framework. What we observe represents only a small part of what is, and what is represents only a tiny portion of what could be.

For Bhaskar, these are the realms of the real, actual, and empirical. “The empirical” is concerned with that which you directly perceive, the information provided to you through your senses or innovations in technology. The things you see, taste, touch, hear, and smell, as well as data collected through machines such as brain scans, mass spectrometers, or other material measures. “The actual” refers to that which exists, regardless of if it have been directly observed or not. So the ant colony, or your subjective experience of consciousness would fall into this category. A brain scan can’t tell you the thoughts running through your head any more than an inventory of ants can tell you anything about the colony that they are a part of. There are certain aspects of reality which may exist on the ontological level, but they cannot be observed through empirical methods. Finally, is the domain of “the real”, which is concerned with metaphysics and the casual mechanisms and consistent structures which generate events. This would be complexity theory, as discussed in the previous chapter. “The real” doesn’t care about who, what, when or where, only how and why. You can think of an iceberg as a useful metaphor. “The empirical” is the tip of the iceberg, which sticks out above the water and is easily observed. “The actual” is the rest of the iceberg, hidden underwater, out of sight and out of mind. And “the real” are the generative mechanisms which caused the iceberg to form in the first place—the physical, chemical, and mathematical characteristics which would cause any iceberg to form, not just the one you are currently observing.

So, if the empirical is only one aspect of a much larger picture, how are we to gain insight into the nonmaterial, non-observable realms? Well, there is an important distinction in definitions I want to draw your attention to. There is a difference between empiricism and epistemology. Epistemology is concerned with what we know and how we can know it. Whereas empiricism is focused exclusively on knowledge obtained through sensory experience. Traditional scientific methodologies emphasize that which is measurable, material, and empirical. But this limited formulation leaves out the fact that valuable information can also be gained through our minds. It is not enough to merely experience things, those experiences must also be integrated into a comprehensive whole, which requires moving beyond the empirical and towards the domains of the ontological and metaphysical. This is the key insight a critical realist approach provides: our sensory knowledge may be limited, but our minds still allow us to make meaningful inferences.

This is what is known as abductive, or retroductive reasoning. Unlike deduction, which goes from the general to the particular, or induction, which attempts to go from the particular to the general, retroduction implies a regression (rather than a progression) in causal thinking. It is a form of inferential reasoning where events are explained by postulating and identifying the potential mechanisms which are capable of producing them. It’s how a detective pieces together clues at a crime scene: DNA is collected, interviews are conducted, testimonies are corroborated, and criminals are profiled. No one piece of evidence is enough to tell the whole story, a “big picture” interpretation is required to integrate all of the various clues successfully. The goal is to develop an account of reality that carries the most explanatory power, but a number of different methodologies are available to draw from. It’s not just the hard evidence that matters, and a lack of evidence doesn’t automatically mean someone is innocent. Motives and meaningful relationships between actors must also be considered. So if that’s the case, how does a detective know whodunnit?

This brings us to the final tenet of critical realism, which is “judgemental rationality”, a term developed to represent the idea that although a variety of methods are available to acquire information, we need not embrace relativism as we attempt to assess reality.

Our understanding of the world may be limited, but truth is objective. Therefore there must be some consistent criteria we can use to evaluate the likelihood of a theory. To return to our detective example, a good theory is one which takes into account all of the available clues and information to provide a compelling chronicle of events. The best descriptions provide the most explanatory power while being able to withstand criticism and critique. For instance, if a piece of DNA evidence is found at the scene of a crime but the suspect has an airtight alibi, then there must be some alternative explanation as to how it got there. There may be conflicting clues, but that doesn’t mean that there isn’t one true series of events which caused all of them to come about. What we want is a theory that integrates all available evidence most persuasively, and these theories can be refined and developed over time as new information is acquired. The point is that we are capable of exercising rational judgement and being persuaded by the best argument. However, this rational capacity is dependent upon what sort of evidence is provided to support a given claim, as well as the explanatory frameworks being used to contextualize available information. Evidence alone is not enough, interpretation matters too! So what implications does a philosophy of critical realism have on how we acquire knowledge?

Part Three: Social Science

I’ve got a bone to pick with social sciences, and I’m going to take this opportunity to air my grievances. But first, what do I mean when I say “science”? I am referring specifically to information acquired through the scientific method. This being the standardized process of collecting and analyzing data to generate predictive results, usually by using experiments wherein variables can be controlled and manipulated to identify cause and effect relationships. In the natural world, this process has worked quite well. Physicists, chemists, and biologists have all been able to use scientific experiments to gain meaningful knowledge about the natural world, and we have the scientific method to thank for much of the progress we seen in the past few hundred years. So it makes sense that social theorists would try to replicate the success of science in the social realm. And replicate they have! These days psychological, sociological, and political research is dominated by studies, charts, and statistics. They make up the basis of university textbooks, social theories, and political debate. There’s only one problem—I don’t think it’s working. Let me give you some examples…

Starting with statistics; these are numerical measures of some social variable, usually collected through census data or large scale surveys. People love using statistics to make an argument. We’re all familiar with the numbers associated with things like the wage gap, wealth inequality, or police brutality. The only problem is that statistics alone don’t actually say anything meaningful about the phenomena they describe. They must be contextualized into a broader framework that allows you to make sense of them. For instance, the same piece of evidence—that women make $0.77 for every dollar a man makes—could be used to support feminist arguments demonstrating sexism in the work place, or an evolutionary psychologist’s position that men and women have different career interests. It doesn’t actually matter what the statistic is, analysis comes from how it’s framed. The fact that the top 1% of income earners hold 50% of the wealth is, in and of itself, a value-neutral statement. However, if you start with the assumption that wealth should be normally distributed, this fact is going to seem like an indication of a dysfunctional economy. Whereas if you’re familiar with how complex systems tend towards 80/20 distributions, then you’ll know that income inequality actually means the system is working as expected. The question remains as to if this is a desirable state of affairs, but these conclusions cannot be reached through statistical analysis alone.

The second model often employed by the social sciences is correlational research; where one takes two data sets and analyzes them to try to infer a causal relationship. As many know, the problem with correlations is that while any causal relationship can be demonstrated through correlational data, correlation alone does indicate causation.

Even when two variables are related, this may be due to a third factor that hasn’t been accounted for, or both variables may be indirect measures of one underlying cause. Moreover, the vast majority of correlational research is used to confirm commonsense inferences rather than to discover surprising associations. For instance, some study that demonstrates a positive correlation between reading and vocabulary size isn’t conducting groundbreaking research, it’s simply “scienceifying” a fact that anyone could have told you for free. This overemphasis on applying scientific methods to commonsense knowledge isn’t actually doing science, it’s just wasting time. The scientific method isn’t valuable because it confirms information we already know, its utility comes from its ability to reveal unexpected relationships, which can only be achieved through the OG scientific method—experimentation.

Hopefully you already know that experiments work by systematically controlling and manipulating variables in order to detect cause and effect relationships. This works extremely well in closed systems (which is what natural science tends to study), but completely falls apart when applied to social ones. This occurs due to the object of inquiry. As it turns out, people are much different than rocks, rats, or nuclear reactors. We are conscious agents, and the content of our mind matters. Memories, experiences, and expectations all play a meaningful role in determining our behaviour. You can’t conduct the same experiment on the same person twice, and you can’t compare results between subjects, either. Controlling for external sociological factors doesn’t diminish psychological or biological ones—it amplifies them. Even if you were to come up with some unethical scenario where you take identical twins and raise them in a lab so you could conduct experiments without any potential confounds, the highly controlled nature of the study would make the results ungeneralizable to the general population! People are complex systems, meaning our behaviour is motivated by a plurality of factors that cannot easily be disentangled.

There is a fundamental difference in kind which separates the social world from the natural realm. People are self-interpreting and value-oriented agents. Not only do a multiplicity of factors motivate any given decision, but people are often highly unaware of what these factors are or could be. Practicing social science requires operationalizing variables which are, by definition, subjective and context dependent. Unlike objective qualities like weight or temperature, there is no way to measure a concept such as happiness or anxiety, nevermind a metric that would allow you to compare subjective experiences across individuals. Unlike the natural sciences, wherein the objects of inquiry are independent from the aspirations of the researcher, social science both defines and influences social reality. Consider the increased discussion about mental health over the past decade or two. The rise in conversations about mental health causes people to introspect and potentially identify mental health issues in themselves, causing reports of mental health problems to increase and more people to be discussing it. The analysis becomes a self-perpetuating feedback loop.

Another problem of social science is that it is impossible to isolate any phenomena down to a simple cause and effect relationship between two variables. Experiments relies upon “closed systems”, wherein one variable can be manipulated at a time while controlling for all others. Being able to exercise perfect control over passive agents is what allows the scientific method to produce predictive and replicable results. People, however, are much more complex than the objects of natural scientific study. Their actions are informed by a lifetime of experiences, expectations, interpretations, and biological mechanisms. It would be highly unethical to conduct a study which would attempt to control for all of these factors, and even then people have unique genetic predispositions which would only be augmented by controlling for all other variables. Given the near infinite amount of potential confounds at play, is becomes impossible to falsify a given claim. For a scientific theory to be valid it must be disprovable, however a theory tested through social research can always attribute failure to the existence of a confounding variable to justify an unfavourable result.

While many social scientists would readily admit that their findings are not nearly as precise, predictive, or objective as their natural scientific counterparts, few recognize that their research may actually be doing more harm than good. There is a disconnect between the philosophy of social science, which recognizes this fundamental difference in kind, and the practice of social science, which remains committed to a scientific ideal. The problem with social science is that it seeks to draw direct, 1:1 causal relationships between phenomena, rather than examining how a complex set of interactions lead to the emergence of social behaviour. There is never one absolute, universal law at play, and any attempt to define such rules is only a partial truth which overlooks how a multiplicity of factors are required to shape social action. Therefore, any fact distilled from social research threatens to oversimplify and obscure the more nuanced aspects of social reality.

This is not to suggest that there are never any causal relationships that exist between social factors, but they are never all encompassing. Correlations represent averages, rather than consistent absolutes. Personal agency and belief simply influence too much of the picture. Take an issue like the use of corporal punishment on children; physically reprimanding them for bad behaviour. Nowadays it is generally accepted that this is not productive, bad for a child's psyche, and does more harm than good. However, there are still millions of people who were abused as children and went on to have successful lives, some of whom would attribute their resilience as directly due to their rough childhood. Although you can’t conduct a scientific experiment to prove that empirically, it makes sense intuitively. Acquiring the tools to overcome adversity makes us stronger and better at dealing with later obstacles. But clearly this principle doesn’t apply to everyone. It is entirely dependent upon the child and their personal capacity to redirect struggle into success. This could be from genetic predispositions, social factors, or internal ones. Maybe reading a certain book is all it took for someone

to begin reclaiming and integrating their experience. The point is that any number of factors could or could not play a role in shaping human behaviour. While one person may find massive success in spite of their upbringing, another might end up with a slew of mental health, attachment, and addiction issues.

On the flip side, too much care and coddling can also result in adults that are not well equipped to deal with the world as they grow older. Children raised by overprotective, helicopter parents are also more at risk to experience anxiety and depression later on in life. A lack of personal responsibility, autonomy, and agency isn’t good for anyone either. You’ll notice that I may be using facts derived through social research, certain correlations and relationships, but I am situating them inside of a broader explanatory framework. And I am not trying to argue that any one behaviour consistently leads to a given result. Alternatively, I am trying to demonstrate that different upbringings all along the social continuum, from extremely negligent to extremely overbearing, can have positive, negative, and neutral outcomes. It always depends upon the individual, their life story and lived experience. Certain factors may make a person more or less likely to result in a given outcome, but there are always going to be stories of people who gained more maturity and resolve due to the exact same reasons. Personal agency and experience is always the main driving force behind any series of behaviours. You can never use one to derive the other; the relationships are always complex, entangled, and interrelated.

I want to be clear that when I talk about social science, I am specifically referring to research that seeks to demonstrate causal relationships between two socially defined variables. There is plenty of room for meaningful scientific research to be conducted in the realms of biology and neurology. We can conduct brain imaging research that correlates different regions with mental states, or test phenomena like reaction times and memory. This type of research is still more difficult because of the confounding social and psychological factors at play, but at least it’s tethered to objective measures of reality. Cognitive psychology studies suggest that our working memory consists of 7 units, plus or minus two. But our minds are like a muscle; the more we practice a task the better at it we become. Waitresses who work without notepads probably have a better working memory than your average Joe, and there are master memorizers who can commit an entire deck of cards to memory within minutes. There may be norms, but there are also always meaningful exceptions. Psychology lacks the absolute laws like there are in mathematics, physics, chemistry or biology. An unwatered plant will die, I’ve heard that e=mc^2, and two plus two definitely make four. In the social world, there are no such definite rules; the more abstract the concepts become the more room there is for uncertainty and interpretation.